Notes from The Sigh Press Editors

Mundy Walsh & Lyall Harris

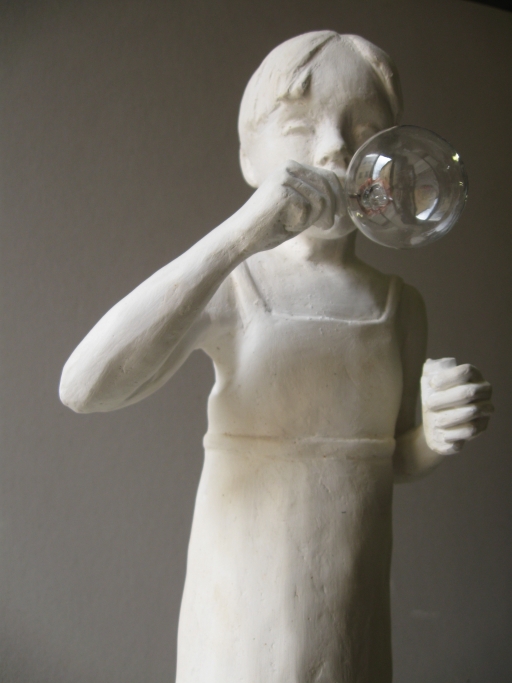

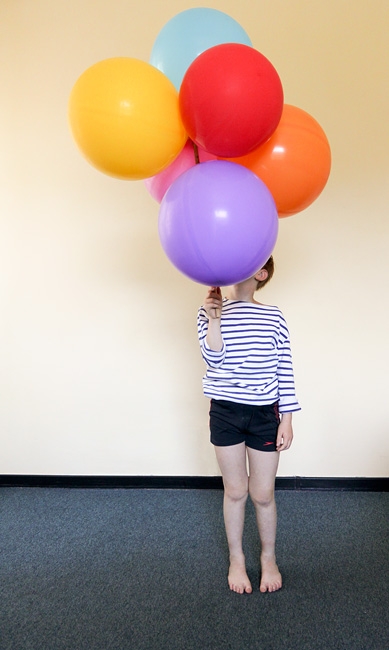

We hope you’ve had a chance to get to know Colleen McKee via her generous answers in our Ampersand 10 interview. McKee contributes new fiction and poetry to this issue and you’ll find further interpretations of the current theme—“Circus”—in the vivid short fiction by Salvatore Difalco, who also provides a wonderfully apropos Cultural Commentary. French- Italian artist Jeanne Isabelle Cornière enriches our pages this season with delicately rendered work, including a few photographs we couldn’t resist.

Look for our next Ampersand interview later this fall and please visit thesighpress.com for our next issue theme and submission deadline. We post at least three times a week on our Facebook page.

Read about the contributors to this issue here and see the PDF version of this issue at The Journal.

Subscribe to our newsletter, where you’ll receive the latest issues, Ampersand interviews and news:

Contents

*

!

‘

–

´

?

*

Blanche Neige

!

THE STRONG MAN AND THE BEAST

COLLEEN MCKEE

Excerpt from the novel in progress, The Strong Man and the Beasts, about a Jewish circus in the late 1920s. In this scene, Sarah, the fashion-conscious, sophisticated bearded lady from Vienna, is disappointed while shopping in a Jewish small town market in Poland.

“Ow!” cried Sarah, clutching her cheek. “Du starker! Thug!”

“What is it?” said the boy’s father, whipping his curly head from the table of tools he’d been inspecting.

Instantly the teenage boy began to run, but his father caught him. He was as burly as the boy was lanky.

“He pulled my beard!” said Sarah. “And he has my ribbon!”

“What?” yelled the father. “You beast! You think you can just grab a lady?” Slap! “A lady you don’t even know?” Slap! “In front of the gantze welt, where everyone can see?” Slap slap slap!

“And he stole my ribbon,” Sarah reminded him. “My ribbon that was in my beard.” She pointed at the undone braid in her beard, which no longer matched the other three braids in her beard, each of which was still tied with a pink ribbon.

“And a ganuf! On top of everything else, my son is a thief!” He shook the son.

“I would like my ribbon please,” said Sarah with dignity.

“Yoyneh, give it to the lady.”

The boy, now redfaced and trembling, held out the ribbon.

“Apologize.”

“Bitte entshuldigung mir,” he said, avoiding her eyes. Sarah took the ribbon carefully, not touching his fingers.

“Bitte,” echoed the father. “Please excuse me. My son is a fool, what I did wrong I don’t know.”

Sarah nodded curtly and left. It was a cold and muddy day in the market and she was too angry to stay. But she still heard the father yelling as she walked away.

“Yoyneh, why? Why did you do this?”

“I wanted to know if it was real.”

“But you knew it was a real lady! If the beard came off it would still be a real lady, no?”

“I thought maybe she wasn’t a real lady.”

“You thought she was a man?”

“No, not exactly.”

“Then you were touching a lady! Do you want everyone to think you’re a starker? Grabbing women in the market?”

“Father, she had a beard!”

“That should concern you like last year’s snow. A lot of Jewish daughters have a bissl mustache. Are you going to grab every girl you see with a little hair on her face? I can’t take you anywhere! Come with me, shnell.”

“I thought we were getting knishes.”

“We’re not getting anything, I’m so embarrassed!”

Bissl (Yiddish): a little

Bitte (Yiddish/German): Please

Bitte entschuldigung mir (Yiddish/German): Please excuse me Gantze velt (German/Yiddish): the whole world

Schnell (German/Yiddish): quickly

Starker (Yiddish): strong man/thug

Mid-1920s: Shlomo has been the Yiddish Family Circus Strong Man for a few years at this point and was enjoying a taste of success until he was unpleasantly surprised one morning to find that as he slept, his foot had been transformed into a restless furry animal. About a week later, the circus went to Vienna, where they were already scheduled to perform.

Pietro, along with Sarah, a bearded lady, manages the circus. He is an Italian convert to Judaism and speaks Italian, German, and (awkwardly) Yiddish. Gilde, the trapeze artist, is Shlomo’s girlfriend. Shlomo and Gilde are from small villages and, unlike Pietro and Sarah, are not well-educated.

This scene takes place the day after their arrival in Vienna. Shlomo has been experimenting with hiding the animal growing out of his leg in an oversized sock; he has been forced to accept using crutches to walk.

Pietro found Shlomo in the café next door to the apartment. Shlomo was slurping coffee and reading a Yiddish newspaper.

“Look, Shlomo! This is what I found at the library.”

“You went to the library already?”

“Some people wake up before 11 o’clock.”

“Not circus people.”

“Look!” He pulled a piece of paper from a large envelope and set it on the table.

“What does it say? You drew this?”

“I traced it.”

The animal in the picture looked much the same as the one now asleep where Shlomo’s foot once was—the same dark, plushy fur, the same head with a long pink nose, the outsized bony hands. It did not make Shlomo feel better to know that someone else had seen this creature, that it truly existed in the world.

“What does it say? This is German?”

“Yes,” said Pietro. “It says—”

“Git morgen!” Sarah said happily opening the door. She had jade green ribbons in her beard to match her dress. Gilde was behind her, a red bow in her blonde hair and a matching ribbon around her wrist.

Shlomo was unpleasantly reminded of his mother, who would help pregnant women tie red ribbons around their doorways and crib bars to ward off demons. Gilde gave Shlomo a kiss on the cheek. She couldn’t be pregnant, could she? She looked as slim as ever.

“Ah, I smell mélange!” said Sarah kissing Pietro on both cheeks. “Why did I ever leave Vienna when we have coffee like this?”

Of course all the customers stared at her beard. Sarah gave them her winningest smile, as though they were already fans.

“My little lady in red!” Shlomo squeezed Gilde. “Sarah put these ribbons in your hair?”

“That’s right!” said Sarah. “Aren’t they lovely with that golden hair?”

“Yes, of course. It’s just for fashion, these ribbons? I know Vienna is a fashionable place. Sheyne dress.”

“It’s silk. What is this?” Gilde said looking at Pietro’s drawing.

“It’s like the animal on Shlomo’s foot,” whispered Pietro. “I copied it from the encyclopedia at the library. It says it’s a Maulwurf.”

“What?” said Sarah, sitting down with some menus. “Are you talking about the vorem?”

“Vorem?!” Shlomo banged his fist on the table, clattering mélange cups. “Would you quit calling it a worm? It’s not a worm! It has hair! It has hands! It has—feelings!”

Everyone was silent.

Then Sarah said, brushing her fingers through her beard, “You don’t have to yell, Shlomo. You think the whole world is deaf? I’m from the city. We don’t have these creatures in Vienna.”

“You do now,” said Gilde.

“The encyclopedia says they live underground,” said Pietro. “They damage farmers’ crops.”

“The book says they are demons?” whispered Gilde.

“No!” Pietro said. “It’s a scientific encyclopedia!”

Gilde stared at him with her big green eyes. “The book says they are not demons?”

“No, it doesn’t say they’re not demons. It’s—”

“You said they came from sheol.”

“I said they live under the earth!”

Giselde snatched the piece of paper from Sarah, who had begun reading it. Gilde stared uncomprehendingly at the strange script, the ludicrous hands, the long claws. She dropped it like it was on fire and walked away.

“Gilde!” Shlomo grabbed his crutch, but Gilde was out the door.

Sarah opened the door and called out, “Gilde, your mélange! Sweetie, you must try it.”

She got up, taking the two cups of coffee.

“The cups!” said Pietro.

“She needs this,” said Sarah. “I’ll talk to her.”

“Please,” said Shlomo. “Please do.”

After the women left, Shlomo sat with his face in his hands and sighed. “Nu, what else does it say?”

“They can see. They have eyes.”

“You’re serious?”

“Yes. They’re hidden by fur. They’re quite small.” “They must be! What else does it say?”

“They can hear.”

Shlomo nervously wondered if the Maulwurf could hear him when he had insulted him. Then he realized that even if it could hear, that didn’t mean it could understand Yiddish. Still, he didn’t like the idea of it listening.

Shlomo took a deep breath. “Pietro, this book…”

“Yes?”

“Does it say how long this animal lives?”

“Six years.”

Shlomo began to weep.

Pietro reached up to pat him on the shoulder. “My friend! My big strong friend! Don’t cry! We must put our faith in Hashem. G-d gave you the Maulwurf, He must have a reason. He’ll teach us what to do…You should eat. Did you eat? Let’s have some torte.”

“This creature eats torte?”

“I was suggesting torte for you. Vienna is famous for torte.”

“Yes, of course, I’ll try some.” He wiped his nose. “I don’t even want to know what this—”

“Maulwurf.”

“I don’t want to know what it eats.”

Pietro shook his head. “No. Let’s talk of other things. Let’s have some nice torte.”

Hashem (Hebrew): another name for G-d

Maulwurf (German): mole

Mélange (Austrian): Viennese style coffee

Nu (Yiddish): Like “so” or “well”—a way to start a sentence or conversation

Sheol (Hebrew)—a biblical underworld for dead people, like Hades. Demons could also live there—or most anywhere, in Jewish lore.

Sheyna (Yiddish): pretty

Vorem: Yiddish uses this word for many animals including moles, snails and worms.

The Twins

The Twins

WE WILL AMAZE YOU

SALVATORE DIFALCO

Her name was Gabriella and she wore a tutu of yellow organza. People in the crowd wore yellow to commemorate her. She looked Leonardo- serene, arms spread, lovely white arms. The little white pony stood still as she adjusted her feet. Ah, but Gabriella weighed a trifle, a feather. The pony did not stir. Meanwhile, the crimson-clad barker frenzied with the megaphone. “We will amaze you! We will AMAZE you!” Did he not know the elephants would protest? A small stampede would bring down the tents. Did he not know the clowns would rebel and even the little pony, with its shaggy black mane, would bend? All is not included in this sorry tale of broken hearts and broken heads. We strive to be relevant, we strive to be valiant. Sometimes our finest efforts wind up covered with straw and swept off the ring. Sometimes, the miniature poodles sashay on their hind legs like dwarf Rockettes and everyone applauds. Other times, the little car comes along and the clowns spill out, too many to count. Not everyone loves this part of the show. Not everyone knows how much I loved Gabriella.

ORSO

Hand on the ribbon, man. Hand on the yellow ribbon. The bear will only bite you if you look him in the eyes. Trust me on this. The ring in his nose, if I yank the ring in his nose he will relent. I promise he will relent. People pay good money to see the show. People deserve a good show. Hand on the ribbon. Yellow calms him. I know it does. He keeps a stuffed Big Bird in his cage. He loves that thing. He sleeps with it under his head. Yes, his claws have been dulled. And his teeth flattened, so they will not pierce skin. He can still crush your bones, make no mistake. But when he growls, yank the nose-ring. And remember, don’t look him in the eye. He will attack if you look him in the eye, nose-ring or not. I have warned countless assistants not to look him the eye. Do you know where those folks are right now? Exactly.

Ricordi al vento

Le Ballon

THE FLY

COLLEEN MCKEE

I wake from dreams of fickle women

to a fly skimming over my body.

I flail my arms and fall into sleep.

I dream I am saddled

with twenty children, all

in identical tiny red coats. That fly

is kissing the back

of my knee. I kick;

he cycles furiously around me,

half spirals, whirlwinds—why

won’t he leave? The window’s

been open for days, but each

day begins exactly the same—

with the whine of a puny war in my ear

I drift into dreams of mazes and sex,

cities without centers,

tests I can’t pass,

and the fly bounces from hip

to hip, nibbling on my ear

and sucking on my hair,

and I swat: I’m not dead yet.

THE PIGEON

COLLEEN MCKEE

My heart is a pigeon, hiding in the eaves,

a diligent bird, pecking hard rice from the road.

My heart is not a dove. There is nothing

peaceful about it. My heart is common,

aggressive. It struts and it fights. It is missing

feathers. It has only

one golden eye.

Gray as a rain-soaked sidewalk,

sudden flashes of iris iridescence.

Scarlet claws clutch at the curb.

SILENCE

´

WHY MAKE A FILM ON CLOWNS?

SALVATORE DIFALCO

LES BALLONS

Toward the end of Federico Fellini’s charming pseudo-documentary I Clowns (1970), Tristan Remy, “the greatest living circus historian,” joins a group of famous performers at the Café Curieux in Les Halles, the farmers market in Paris, for a lively round-table about the White Clown, a staple of the traditional circus.

In the midst of some sharp back and forth, Remy declares that the great Antonet, with his joyless, authoritarian representation of the White Clown, in effect killed him off—much to the protests of the others at the table. They argue that Antonet continued being funny and provocative despite his darker take. Remy also offers his opinion on the merit of Antonet’s pratfalls, that he never saw him perform one—again to protests.

Watching I Clowns again after many years, I was struck by its lightness of foot and abundance of Felliniesque tropes and humour in small. Here, Fellini checks the grand gestures and fantasia of his more ambitious films, yet he is omnipresent.

For a man who saw it as a perfect metaphor for life, Fellini’s minor obsession with the circus, evident from La Strada onward, finds fresh intimacy in I Clowns. Yet, even in a film as scaled-down and heartfelt as this one, the former caricaturist was never far from satire. Capriccio rules even his most earnest work.

Clowns, as Fellini knew, have always provoked ambivalence. Think Feste in Twelfth Night. And they have never been shy about their darker drives and energies: Canio of Pagliacci comes to mind. For a brief time, the gentler clowns of the Ringling Brothers, Red Skelton and the dentist’s office made us smile and even brought us some comfort. Times have changed.

We were already well along a dark road with the Insane Clown Posse, the first incarnation of Stephen King’s It and the “creepy clown” phenomenon. Then they reprised It—made it madder and darker—and rebranded the clown as a totally sinister figure.

At one point Tristan Remy turns to the narrator/director of I Clowns, that is to say Fellini, and asks, “Why make a film on clowns? The circus world no longer exists. The circus no longer has any meaning in our society.”

A rather prophetic statement uttered half a century ago, given the recent demise of the Ringling Brothers. Perhaps the traditional circus no longer has any meaning to a society that more and more has become itself some kind of technological circus, with unceasing and ever-escalating spectacle available 24/7.

All that said, I was most struck, revisiting I Clowns after many years, by the film’s inescapable sadness. It can be viewed both as a gently satirical homage to the dying art and tradition of clowning. Or perhaps, keeping in mind Fellini’s visionary bent, I Clowns may be a harbinger of a time when clowns, having lost their franchise and sense of humour, turn authoritarian, and sinister.

?

What is revealed by the unmasked circus?

BLEU / INFINITO 2

ISSUE 19 • Winter 2018 will be published in December.

Visit www.thesighpress.com for details.

© 2018 THE SIGH PRESS

None of the work published by The Sigh Press may be copied

for purposes other than reviews without the author and artist’s written permission.