Notes from The Sigh Press Editors

Mundy Walsh & Lyall Harris

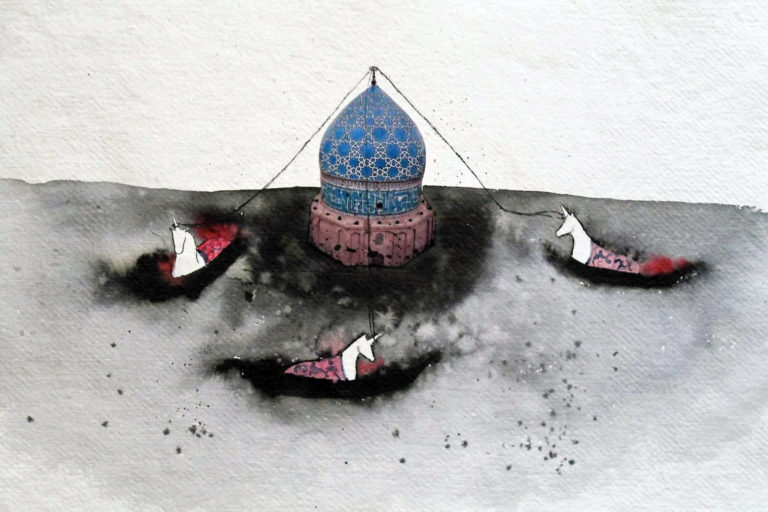

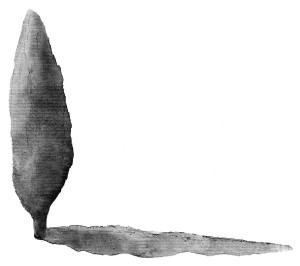

Over the winter holidays, curl up with interviews from our Ampersand series! Our last interview was with Kamin Mohammadi who, in this issue, contributes Biological Clock, a personal essay Mohammadi braves with humor and heartbreaking honesty. Images by Maryam Rastghalam, another Iranian-born artist now living in Italy, seem to emerge from dreams, existing somewhere between magic and memory. Poems in the issue by Peyton Prater Stark inhabit a similar space with works that are urgent just as they slip through your fingers.

Our next Ampersand interview will appear in early spring 2018. We are very excited to have the chance to pose questions to internationally recognized and award-winning poet Alicia Ostriker.

Please visit Submissions for our Winter Issue theme and deadline and our Facebook page where we post at least three times a week.

Read about the contributors of this issue here and see the PDF version of this issue at The Journal.

Subscribe to our newsletter, where you’ll receive the latest issues, Ampersand interviews and news:

Contents

*

[ ]

,

?

*

Floating Dome

[ ]

BIOLOGICAL CLOCK

KAMIN MOHAMMADI

Persian Garden

He holds my hand as we walk in. It is a surprise every time. When I come in through the hospital doors from parking the car, he is there by the entrance, another elderly body sitting on the row of plastic chairs, all frail, all waiting for someone to come and take charge of them. He looks up expectantly, his face breaking with recognition when he sees mine, with a relief that now he knows what to do, where to go, who to follow. I hold out my hand and he wordlessly places his inside mine. The hand of my father, the skin stretched like delicate gauze over the fine bones and tendons of his hand. His nails are well kept and the skin soft – my mother meticulously oils his whole body after he showers; she looks after him well. I have never held my father’s hand before, at least not in living memory.

We shuffle down the corridor, I match my pace to his. He moves unsurely, leaning on me just enough to give him the reassurance he needs to place one foot in front of the other. We pass men in wheelchairs, their papery yellow skin flaky, their emaciated bodies slumped in their chairs, and I am grateful that my father can walk unaided, no chair, no stick, just his unsure shuffle made a little more sure by my presence.

Upstairs in the clinic I line up for him while he goes and sits down on another plastic chair. The queue is always long, there is always an argument, someone is always late or has the wrong paperwork or has just spent 20 minutes queuing at the wrong clinic and won’t be appeased. I wait in line with the old and the infirm, and I watch my father as he sits, haplessly, waiting for me to do this for him; me the adult and he the child; the inevitable reversal. We wait again, after the receptionist, for the nurse, who weighs him. He sheds his coat and jacket and emerges twig-like from the folds of his coat, his belt sagging on its tightest hole. The nurse writes down his weight on a chart, we compare it with his last appointment. Somehow he has shrunk to 20kg under his normal weight but, somehow, fooled by his locked-in, unchanging habits, we have accepted his new thin brittle form without quite noticing.

My father, now 90, once so powerful, now led by me around the corridors of the hospital from plastic chair to plastic chair, watching me expectantly for guidance. Many of the other patients are also elderly, led around by their children, mostly, I notice, daughters. Many are foreign, migrants who arrived in London many years ago and who adapted to and adopted the ways of the land. My father would never identify himself as an immigrant; so well has his ordered, reserved personality fitted into this ordered, reserved society that he has felt always a part of it, from it, of it, not foreign at all. These elderly patients are invariably flanked by smooth- faced versions of themselves, second generationers who bring their parents to their appointments – proud people rendered uncertain, leaning on their offspring. The mother – if the patient is a mother – is often in her ethnic clothes – a sari, an African dress, a shalwar kamiz – the children, in their contemporary fashions and plump-faced beauty, perfect updates of the aged parent, their ease in this society being the point and reason for their sacrifices; they – we – are evolution in action, in plain sight. We speak, the new generation, with perfect accents, without hesitancy, with sureness. This is what they have paid for, with their migration and homesickness, with starting over and making themselves foreigners, this ease they have given us, this gift of being British in a way that they can never be. And I look at us doing reparations of filial duty for their sacrifices, stepping out to take charge, to help them negotiate the system in the language that is our mother tongue, and it makes me wonder – who will do this for me?

I often wonder what would have happened to my father should we not have kept him. Had my mother thrown him out all those years ago when he betrayed her instead of forgiving him and keeping him so that now that he’s old, he has us to take care of him. What if he was alone now? How would he cope with these appointments, the tests, the failing faculties, everything getting slower, harder to hear, to see, to understand? I know the question I am really asking is: how will I cope with these appointments when my time comes. What if I reach the age of 90, who will hold my hand and lead me through the hospital?

I am 45 and it looks unlikely that I will have children. This decision – or non-decision – is fast shaping up to be a fact as the months pass and the years disappear behind me. It is a subject I rarely think about, and it is only here in the corridors of this hospital, when I bring my father for these appointments, that I visit that place in the distant future where my old age is located and wonder how it will look, what that landscape will be, who will be there with me. My mother had offered, just the other night, to pay for me to have IVF, one last chance at having a baby, at shoring up the future against loneliness and helplessness. If I got pregnant naturally that would be fine – but I didn’t want to seek it out at the end of needles delivering hormone shots. I said no, dashing her hopes of being a granny. At 45, she had said, don’t you feel any maternal longing, any calling from your biological clock?

My biological clock. I’d never heard mine. Or been aware of it ticking. Apparently we all have one, but where was mine? I partied through my twenties laughing out loud any time anyone asked me if I had kids. “Me?” I would say with astonishment. I felt barely older than a child myself, was taken aback that anyone should mistake me for an adult. Had my clock been ticking, I would never have heard it over the thumping bass anyway.

In my thirties I did start to hear the clock. Not mine, I hasten to add, but my friends’. Close girlfriends’ conversations closed in on the topic, they got pregnant, started families – they actually planned these things. I was amazed, and doubly so when the babies started arriving. They were magical, interesting, and they smelt so good. I loved all our babies, and I collected quite a few godchildren. But I still didn’t particularly yearn for one of my own.

I was busy. Working and building a career; it was writing, commissions and book deals which preoccupied me, not babies and setting up home. The only clock I heard was the one ticking out the remaining hours of one writing deadline after another. My best friend Clare described her own wish for a baby not as a ticking clock, but as a sort of tsunami of longing which had washed over her one day with such intensely that it had left her breathless. Another friend (two kids, the first of our group to have children) made me promise her that should I be approaching 40 and still alone then she could help me choose a sperm donor and operate the turkey baster… I played along but I was so appalled with this suggestion that I quietly cut her out of my life, so that, by the approach of 40 some five years later, she and her turkey baster had disappeared from my circle.

As my 30s wore on, it did start to seem odd that there was no sign of this ticking, no tsunami, not even the faintest desire. No tick and definitely no tock. I had nothing against babies, and was a pretty good godmother to all my little ones, spending lots of time with them and having them round on Sunday afternoons. But, like any sane person, when they left after these visits, I breathed a sigh of relief as I tidied up the devastation and thanked God that I could give my delightful godchildren back after a few hours.

And then, there was the longing to write. This eventually crystallised into one solid idea, The Book. This was my tsunami of desire. The commission came when I was 37, and in the years I should have been thinking urgently about finding a man and having a baby, I preoccupied myself with giving birth to a book. Not just any book, but The Book, the one I had always wanted to write, the one about my past and my family, my country Iran and the heartbreak. Patient friends, the audience for so many of my complicated family stories, had begged me to write this book for years, tired of trying to follow the Iranian names and web of family relationships. Just as I should have been reaching out into the world to find a mate and build a family, I closed myself away and instead reached deep inside myself to tell my family story and heal the wound of the revolution and having to leave Iran. And it worked, my book was published as Mille farfalle nel sole in 2012 and I emerged whole and happy – and 42. That clock should have been ticking wildly by now but I still heard nothing.

Along the way I had ended up living in Italy and fallen in love too. I met Antonio when I was 39, was just coming up for air after delivering the first draft and was looking for nothing so much as a bit of fun in my new town of Florence, where I had fled to write and where I had decided to stay, seduced by its beauty, the gentler pace of life and the tastiness of the tomatoes. And Antonio was super fun. Which was lucky because he was also weighed down by two broken marriages and trailed behind him an assortment of children by different mothers. Three children and two mothers to be precise. One of his first statements to me was that he was done with marriage and kids. The kind of declarations men make as they are about to take you to bed, knowing full well you are not really listening, that your mind is on other things, but they put it out there to clear their conscience, to be able to say in the months and years after – “but I TOLD you! It was your choice.”

I took no great notice of Antonio’s statement. Not so much because I wanted marriage and kids but more because I didn’t care; I didn’t take him seriously as a life mate – all those children and ex-wives – and it seemed irrelevant. “Don’t worry,” I had said airily to my mother. “I won’t be falling in love with him, he’s just for fun.”

Famous last words, inevitably. Antonio turned out to have the kindest heart anyone had ever placed in my hands and before long, I too fell in love with him and, slowly over the months and years, I started to take him seriously. So I took on his baggage and found myself a stepmother.

I emerged from the great endeavour that was The Book, returned from my long hard journey inside myself and into my past with this great, surprising love for Antonio and staring down the barrel of the age of 42. There was still no ticking, no great tsunami of longing, not even a stirring of desire for a baby. Now that I had delivered The Book, there was no ticking of any kind in my brain. And Antonio had enough children, frankly, to go round.

Then one day, when we were two years into our blissful co- habitation in the Tuscan countryside, his son moved in with us. Unannounced, over the course of a weekend, it was decided that he would stay and so he did. And suddenly, we were a family, full time parents to a disaffected and troubled teenager. All too suddenly motherhood was on me, unlooked for, unsolicited, unwelcome. Early mornings making toast, evenings cooking family dinners, afternoons at the supermarket filling up on everyone’s favourite foods, making sure there were enough vegetables in the fridge, enough fruit on the table, a trolley- load of duty and obligation. At the same time, The Book had just come out and I was being invited to festivals, talks, interviews – the gratifying glare of publicity was on me and I was jetting back and forth from Italy to Britain to fulfill these obligations. They were fun and we had planned for Antonio to accompany me but now, he was a full-time dad and I was alone on the literary festival circuit. This was not how I had envisaged it. A life without children had to have other compensations – travel, adventure, togetherness, but now, I was on my own for the adventures, just as I had finally found someone I actually wanted to share them with. I had spent a lifetime travelling alone, and it had not daunted me. But now, it bored me to go it alone. It was time for things to change.

After one literary festival, sitting with my best friend Clare on the floor of her sitting room while her toddler played around us, we discussed this.

“Why don’t you have a baby?” she asked as if it was the most reasonable question in the world. “If you have to be a mother and do family life…”

“I might as well do it for my own child?” I had finished her thought. Suddenly it did seem like the most reasonable idea in the world. “OK,” I had agreed, “I’ll have a baby!” We had looked at each other and squealed.

Looking back, that was the sound of my biological clock going off – the squeals of me and Clare laughing on the floor. As close as I got to one any way. No longing, no tsunami, but a lot of reason and a sort of magical conjuring that happened when we cackled together over that decision. Light-hearted as its making seemed, it turned out to be a very serious decision – within two months I was pregnant.

Persian Garden

I look up as they call my father’s name. I nudge him and we go to another room where another nurse checks his blood pressure and other vitals before we are sent back out into the corridor to wait on another set of plastic chairs in another part of the corridor ready for the doctor. We settle into our new seats, there is no conversation. The implacable silence that seared through my childhood and gave me so much angst in my young adulthood has ceased, over time, to feel personal. It has taken many years but it has even grown comfortable, long since accepted. That’s why I am so surprised when my father starts to talk to me, when he turns and asks me what I am working on. My father’s attention seems to swim in and out of focus these days but as I regard him in shock, I see that he is alert, snapped into concentration. I find myself explaining that I am writing an essay on the “biological clock.” I almost blush as I tell him this – this is not the sort of topic that ever rears up between us and I am not sure how to broach any part of it – a good modest Iranian girl and her remote, authoritative father do not discuss such intimacies – so I let the words hang in the air.

To my mounting astonishment, my father – this old, proud and dignified man who is from another world, another generation, born in the first quarter of the last century in the mountains of Kurdistan, so very far from here in every sense – turns to me with a chuckle and says: “If men had biological clocks, then I can say you are the result of mine.” And as I stare at him dumbfounded, my taciturn father starts to talk, to tell me the story of his own biological clock, words cascading from him like a shower of blossoms on the breeze of a late spring day.

On the day in 1964 that my father, Bagher Mohammadi, walked into a colleague’s office to be greeted politely by a new secretary called Sedigheh, he had been mulling over his plans to divorce his first wife, an Englishwoman he had married after graduating from university in Britain. She had been living in Iran with him for more than a decade, but they had failed to have children and the couple had agreed to part. That is how my father put it – his first marriage dismissed and closed down in one sentence.

My father, a preternaturally bright boy from Kurdistan, had been one of the first wave of Iranians who had been handpicked from all around the country to be sent and educated in Britain at the expense of the State – Iran’s hopes for bringing back Western expertise to run its nascent oil industry. My father has described that journey to me before, the long voyage from Iran to Britain in the months after the end of the Second World War. The boy from the remote mountains of Kurdistan now took the train from Iran to Baghdad with two other boys, from there they headed to Beirut and somehow, they wound up in Cairo where demobbed soldiers were thronging to get back home – it took them three weeks to find a passage on a ship to Liverpool. Even now, a lifetime later in a land that barely remembers the realities of that war, my father’s lips still twitch into a smile as he mentions that trip through the Middle East and north Africa, the three weeks in Cairo by the end of which they had all spent the whole of their first year’s allowance. Whatever they did then, those three Iranian boys let loose in the world for the first time, its memory still tickles him. Once my father was back in Iran, with his English bride and British education, he was ready to step in when the British were locked out of their offices in 1953, when the oil industry was nationalised and Iranians took over. When he walked into his colleague’s office in 1964, my father was at the top of his career, a director of the oil company, settled, confident, comfortable in his power. He had lived in Abadan since coming back from Britain, the hot and humid piece of land which had lain in the embrace of tributaries of the rivers Tigris and Euphrates, undisturbed, for thousands of years before being forced out of its languid slumber when oil was discovered nearby; it was deemed the ideal location for the site of the world’s largest oil refinery. Bagher hailed from the cool mountainous climes of Kurdistan and it had taken him some time to get used to the heat, the dust, the humidity, the flies – all the things which had annoyed him so much at first. By the time he met Sedi on that fateful day, he had grown used to Abadan, had even found himself missing it when he went away. Abadanis had a passion born of the fiery heat just as my father contained the chill of those cold Kurdish nights in his soul, and they were the most stylish people in Iran, famous for always wearing their Ray-Bans. I know from pictures of him from then that my father had already adopted this – he is wearing his Ray-Ban Wayfarers in every single shot, his hair Brylcreemed neatly into place. My father had become an Abadani, at least, as much as he could.

My father now tells me that after meeting Sedigheh that day, he found himself making excuses to visit this colleague. Sedi sat at her desk, her thick hair arranged on top of her head in a little beehive, black kohled eyes as was the fashion then, and he told me that he noticed the generosity of her lips and the timbre of her low voice. My mother had a proud Persian nose which had dominated her face as a girl but which she had, in young adulthood, finally grown into, and high chiselled cheekbones now framed her face and contextualised that nose so that it was regal and proud where once it had been overbearing.

To my father, she grew more appealing with each visit, her brown eyes intelligent, her form elegant, her manners correct. My father was now suddenly longing for what he had never had with Audrey – a family, children, what he had never craved before. In his forties, he felt in his prime but he had an inkling that soon it would be too late, he would be too old to lift his baby child up in his arms, to run around after it, to teach it to play football, how to swim in his pool. He felt an increasing urgency to procreate and perhaps it was this that inspired him to behave uncharacteristically romantically.

One day, he tells me, he wandered into his colleague’s office with a rose in his hand, a fragrant damask rose known in Iran as the Mohammadi flower, his namesake. He casually placed it on her desk as he passed by with a nod. The Mohammadi rose is so fragrant that it is the flower the famous Iranian rosewater is made of and the scent of this particular bloom filled Sedi’s office. At first she just sat and just looked at it. She didn’t know what to do with it and so she threw it into the bin, pretending it had never been there. When Bagher came out, he left the office with no word to her and she didn’t know if he had noticed the flower was no longer on her desk.

Bagher certainly had noticed and, unabashed, a few days later he repeated the gesture. Sedi threw the flower away again, but she smiled a little this time, and it had become kind of a game between them, him dropping a Mohammadi flower on her desk several times a week, and her disposing of it without saying anything. One day, when he came out of her boss’ office, he could smell it even before he saw it on her desk: a tiny vase and in it the small pink rose he had delivered that morning. He stopped to take it in, then he smiled at her. Nothing was said, but she looked right up into his eyes and smiled back, and with that began their courtship.

My father stops here. The rest, as they say, is history – family history. How my mother had married wearing a lace mini dress and her trademark beehive, how, a few years later, when my father was at the tail end of his 40s and losing hope, I had finally come along.

“You,” he says to me now, turning to me, “you were my last hope…”

His last hope. And hence my name, which loosely translates to mean something like: “my soul’s desire.” I was the product and function of his biological clock and the glue that had kept him and my mother together through all the difficult years in which their unsuitability for each other had played out.

I want to ask him if he had made the right decision, but I couldn’t. It was too intimate, even for this surprising conversation. Once my mother had told me how, when he had fallen in love with someone else and begged her for a divorce, that when the madness was over and he was back home, he had written her an explanation of what had passed. In order to explain himself he had written an epic poem, talking of his love for my mother and the sudden passion for the other woman which he had, out of duty, eventually snuffed out to return to us. My mother could only focus on the content of this poem, but to me it was remarkable because he had chosen to express himself in one of the most difficult forms of literature to master, and I knew then that my father’s first real and great love had been writing. As if he can read my mind, my father says: “Once I loved writing. But I chose you. You though…” And he patted my hand – a move so surprising I almost drew mine away – and smiled at me. “You write books. You should be proud. Not everyone can do that…”

We sit here on the plastic chairs and I wonder about my own great love. Had things played out as expected after I got pregnant in 2012, I would now be naming my son as my great love with no hesitation. But the one and only time my biological clock nudged me, things didn’t go according to plan and now, as I sit here with my father, I remain a daughter but not a mother. I will never be a mother.

I remember the happiness, the fear of telling Antonio of my pregnancy, of the way he had embraced me – and the news – with such joy. I remember how the world had opened up around me – suddenly things which had never felt relevant took on a new importance; even a change in the government’s education policy was now fascinating. I remember how I saw pregnant women everywhere and I remember how scared I had been the whole time but also how excited – unreasonably, unaccountably, instinctively full of joy. It was the hormones of course – the same chemicals that made pregnant sex so explosive made everything suddenly meaningful and somehow light, easy, manageable. Somewhere in my hormone-addled brain everything made sense, life fell into place – even though it had not been out of place before. Although we had a lot of practical decisions to make – which country would we eventually live in, would we get married, when would we tell Antonio’s other children – the bigger picture had pulled into focus, a biological imperative being fulfilled. So natural, so normal – the first time I have ever done anything expected, natural. The part of my brain not flooded by the happy hormones watched all this and marvelled at how easy life was if you just followed the biological imperative, if you didn’t struggle for fulfilment in the dark unknown corners of your soul and followed the set path.

Then, a good four months into the pregnancy, just as I was starting to show, the shattering news. Our babe would be severely handicapped – there would be no chance of him living a life by himself, and no way to tell how long he could live at all. We were offered a termination and we made our decision without much hesitation. A river of tears flowed through every breath we took as we lived through the days leading up to the operation; our decision to terminate the pregnancy was heartbreaking but we were not conflicted. We would try again, I would get pregnant again and have a healthy baby and it would be fine. I was only 42. It still felt like it would be easy. It would be fine. We would be fine, we would make a family soon, not right now, but soon.

And yet, as they wheeled me away from a sobbing Antonio and into the operating theatre, I cried so hard I started to hyperventilate. The anaesthetist, her red hair tied back and a mask on her face, held my hand to calm me down, her eyes filled with compassionate tears as she administered the anaesthetic. When I woke up a second later, my hand went to my tummy even before I registered that I was in a different room. It was empty, my stomach was flat, void of what had been there. It was empty. I was empty. My baby was gone. I felt it immediately even before I knew that it was over and I was in the recovery room and life could go on as normal, could go back to normal.

I went home to Italy after that. And I was surprised by what I found there. My teenage stepson greeted me with a warm hug, looked me in the eye and said how sorry he was for my loss, for our loss. My stepdaughters – who knew I had been in hospital but not what for – rang and messaged impatiently until the weekend came when they were with us, and when they arrived, they ran to me, their faces a mixture of worry and wonder. They treated me as if I was a delicate, breakable thing and only hugged me when I told them it was fine, I was fine, there was no reason to treat me differently, I was not hurt.

Now as I sit with my father, I know that actually, I had been hurt. My heart was broken. I had been heartbroken. But in the midst of all the heightened emotion, I had been stunned by more than the pain of loss. In my vulnerability I had also been surprised by the realisation that here, already, was a family. Like them or not, these kids of Antonio’s by now belonged to me too, just as I belonged to them. This was my family. I hadn’t chosen them, given birth to them, embraced motherhood for their sakes but here they were anyway, not a biological imperative, but a labour of love. I had thought of being a stepmother as a choice, but now I saw that it was as random and beautiful as becoming a biological mother – an act of God. And I saw, in the eyes of my stepchildren after my spell in hospital, that weekend as they followed me around, all three of them, as I caught them looking at me sideways with anxiety, that I had a place in their hearts somewhere central enough to make me of extreme importance to them. I had become one of those adults whose being was so fundamental to their own, like my own beloved aunties who had been as crucial to me growing up as my parents. I read somewhere once that in every human society, some 20% of women remain childless, indicating that they – we – are needed for the survival of our species just as much as those bearing the children – the aunties, those vital cogs in the child rearing wheel, with their patience and help and love laced with anarchy.

It wasn’t conventional, it wasn’t primal, but it was a relationship made of enough love, duty and concern to make it familial.

The years have passed and no new pregnancy has announced itself. I have grieved, I now realise, quietly for the four years since. I have looked with longing at every pregnant woman, I have inhaled deeply the scent of every fresh-born baby, I have regarded with envy my friends with their conventional families and their conventional lives. But when I had an idea that broke through the grief enough to take me back to my computer, to pull me out of bed in the mornings in order to pour out the words that would stay in no more, I knew that the healing had begun and slowly the envy of those conventional families evaporated and in its place my usual passions bubbled up: travel, adventure, literature. I wrote a proposal, got a book deal, signed a new contract. Went back to my desk. Sitting here with my father now in this plastic chair, I am worrying not about my child or gripped in panic at the ticking of my biological clock. The tick-tock that haunts me is of my deadline, the delivery I am preoccupied with is of my first draft, and my midwives are my editors. As my father pats my hand, his expression swimming back out of focus as he slips back out of reach into old age and frailty, I smile. For me, this is the way it is, this is my normal, this is my longing, the inner calling I have no choice but to answer: books not babies.

*

Floating Dome

,

THE TEST

PEYTON PRATER STARK

I

the horse nuzzles the edge of the forest like a mother. your feet in the gutter. I hold the grass in my lips and blow. what do I know about hiding? I know a warning when I see one. I know how to braid six strands of it. when I’m caught in a gully I can’t get out. not you or our mother can save me. the brush, its thorns, the light through it, the lattice, its blood draw, its burnish, its deviance, what it tore through, what’s in it, its flowers, how it opens in the morning, how it smells in the rain, how it sprouts, how it winters.

II

you don’t want to play a game but the horse says it’s too late. says all lines are either the sum or the difference. you knew this was true before. the horse calls the rules, says two observers in motion get at most one chance to compare clocks face to face. you feel this most and you throw all your rocks into the river. count the distance between the release of your hand and the plunk of stone into water. you want to remember all the specific moments and their beauty. you know it doesn’t matter if the game is safe.

Floating Dome

III

we think we could spend another fifty years digging up all the things we left. the land was dug up before we got there. which is to say there are things we didn’t buy and things we can’t sell. things we planted and left behind. what we bought with quarters. a wire gate to crawl under. what we displaced for a swing. we make a list of things to leave and end up including everything. making it hard to close the doors. at night we argue about whether to leave at all. and whether there is some sort of real rest. we agree that today we will make a list of what this might look like. letting a fencepost decay, watching it happen.

?

Are you doing what needs to be done?

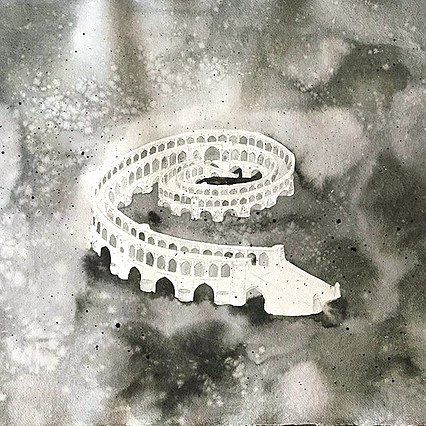

Spiral Bridge

ISSUE 15 • Spring 2017 will be published in March.

Visit www.thesighpress.com for details.

© 2018 THE SIGH PRESS

None of the work published by The Sigh Press may be copied

for purposes other than reviews without the author and artist’s written permission.