Notes from The Sigh Press Editors

Mundy Walsh & Lyall Harris

We hope you’ve had a chance to read the thoughtful answers to our Ampersand 9 interview questions with author Jessie Chaffee. Chaffee contributes new work to this issue as well as an excerpt from her novel Florence in Ecstasy (The Unnamed Press). “Impressions” is our issue theme and you’ll find further interpretations of this in the transportive, atmospheric artwork by Deborah Sibony and in the accomplished poetry of Jeffery Beam.

Look for our next Ampersand interview in late summer 2018. Please visit Submissions for our Autumn Issue theme and deadline and our Facebook page where we post news.

Read about the contributors to this issue here and see the PDF version of this issue at The Journal.

Subscribe to our newsletter, where you’ll receive the latest issues, Ampersand interviews and news:

Contents

*

, –

!

´

?

*

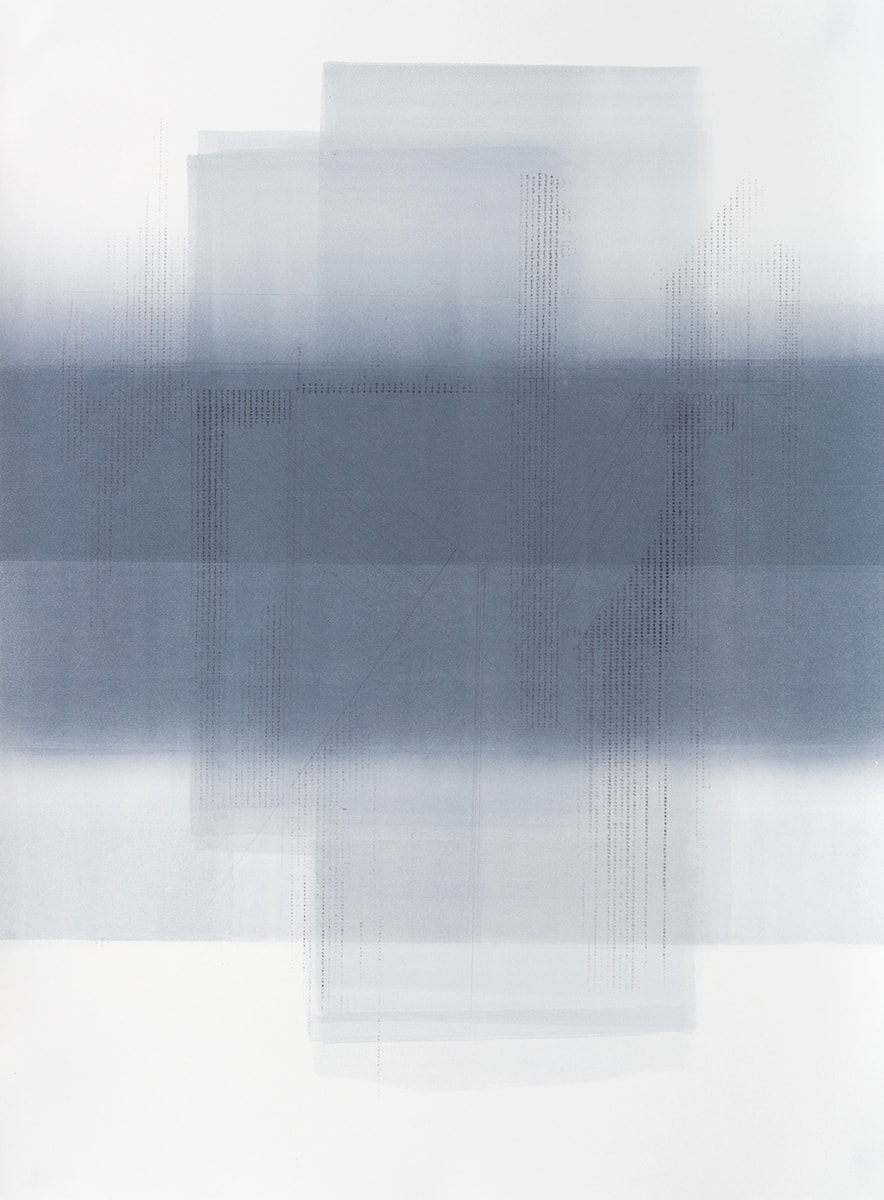

Linear Space

Linear Space

,

BEATA

JESSIE CHAFFEE

Her toes curl up and back, unnatural. Her head, cocked left, is pitched back, too. Rings sit heavy on the bare bones of crossed hands, and a brocaded gown crushes her down to the bottom of the gilded glass coffin, a Snow White never found and now charred with time. But to the town’s residents who fill this place, pew after pew, on this Easter Monday dedicated to this woman, not-quite-preserved, she is beautiful, she is blessed, with the capacity to bless—beata.

And in the third row, a girl whose feet just brush the ground dips her head out into the aisle to watch as the priest breaks the bread of the body over this body, drained of its blood and laid flat in this church perched high in this hill town, one of so many bodies in so many hill towns, preserved to be caged and then revealed, a perpetual rising as they are born on the shoulders of believers and carried to the centers of alters on mornings like this one, exposed to be blessed and to bless.

On one wall of the church, Sant’Agata’s breasts are twisted from her body with hot tongs. On another, Santa Lucia bears on a dessert plate her eyes. This is what this young girl has studied when sitting in this church each Sunday, these women looking out, their bodies separated into parts. Is this how she sees her own body? Not yet. They are still one, she and her body. Though there was that hot afternoon when she cut her finger, and didn’t cry when the blood sprang up, but watched it silently globe on the tip and maybe then, in that moment, she thought that her body might be something else after all, that she might be someone with the capacity to bless.

The service is over and now a line forms, two wide, down the aisle and out the church’s doors as the crowd waits patiently to circle and circle this body. The girl shuffles beside her father and watches a woman with brimming eyes who whispers emphatically, her fingers extended, pleading. Watches the old couple who slowly circle the beata, then stand at her feet, mouthing silently the loss she was unable to spare them from, and still, year after year, they come. Watches the teenaged boy who fumbles and fumbles his candle, lighting and relighting to place it, shaking, amidst the many other quivering flames, so many that from where the young girl stands, the beata floats on a river of light. She watches them circle, watches this body rising and rising in its transparent vessel until she feels herself rising, too, lifted by her father to face those hollowed and hallowed eyes, to place her small lips on cold glass, to imagine they might traverse the space between.

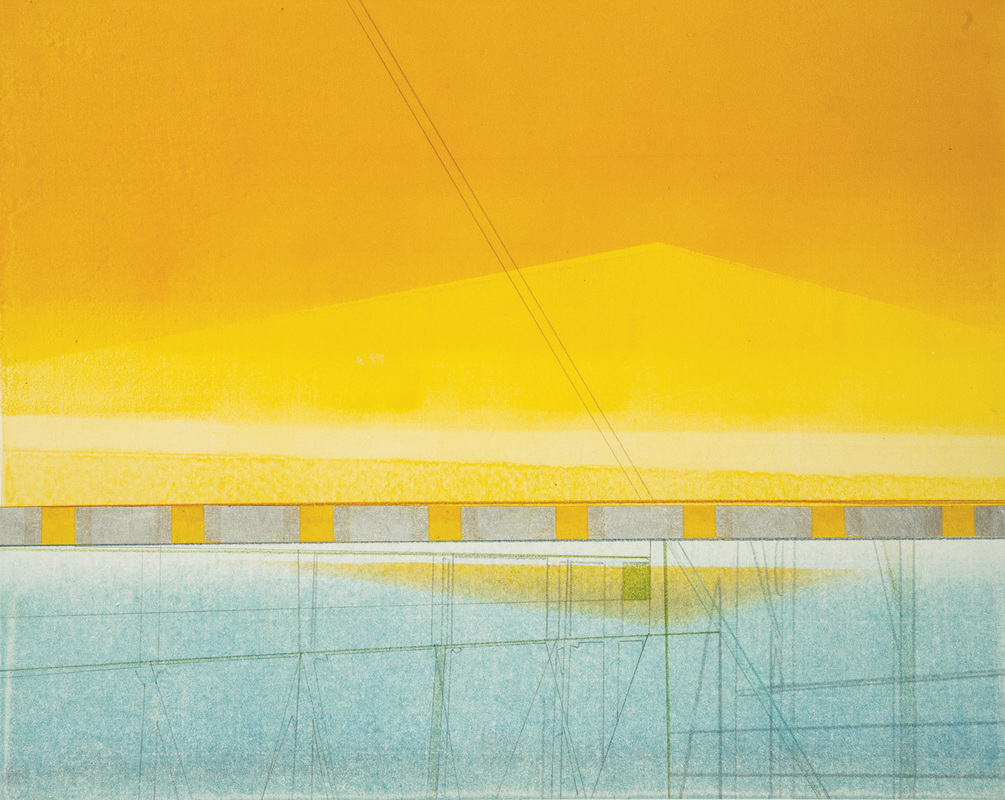

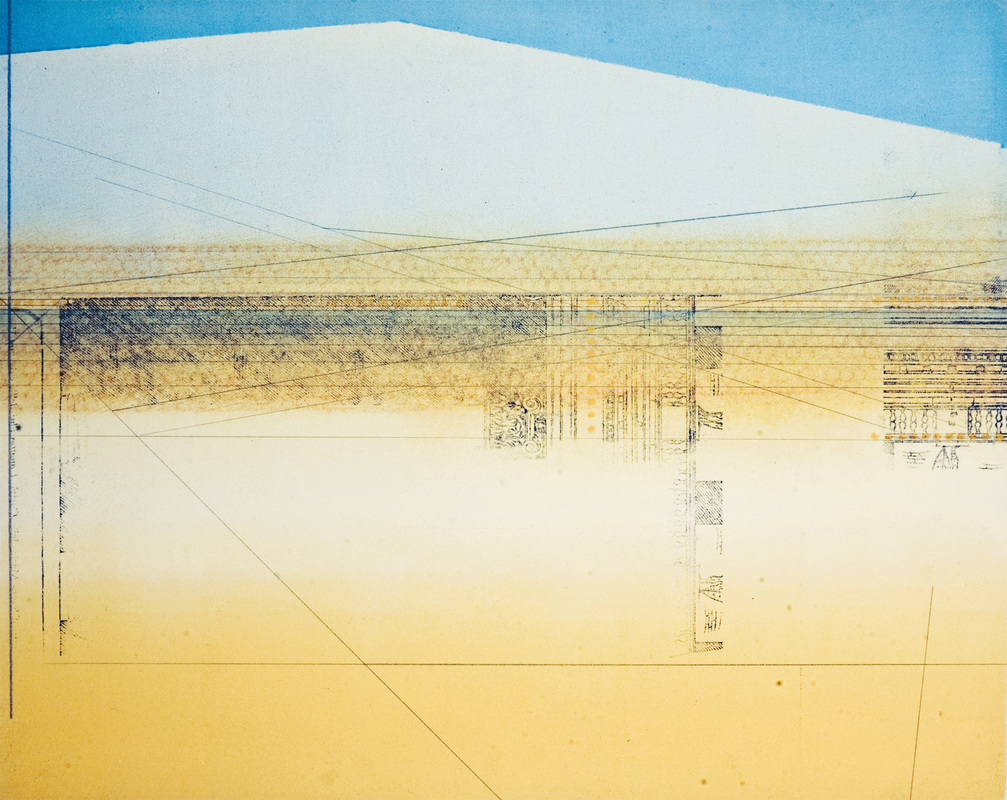

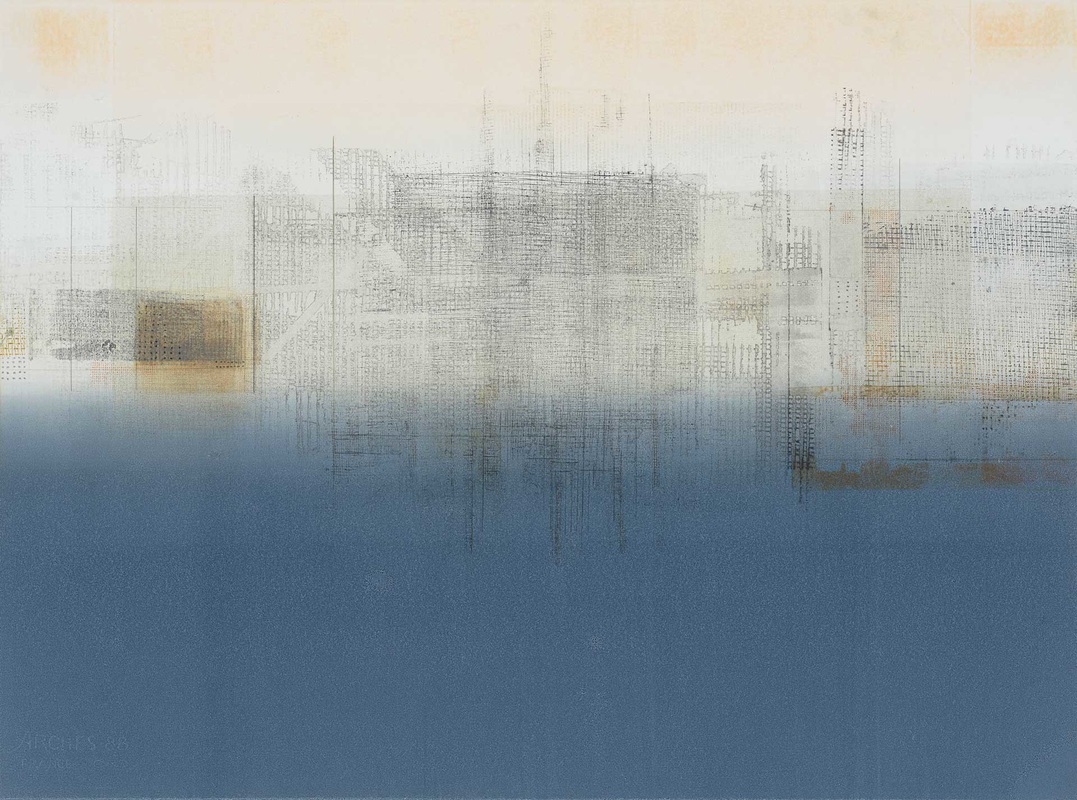

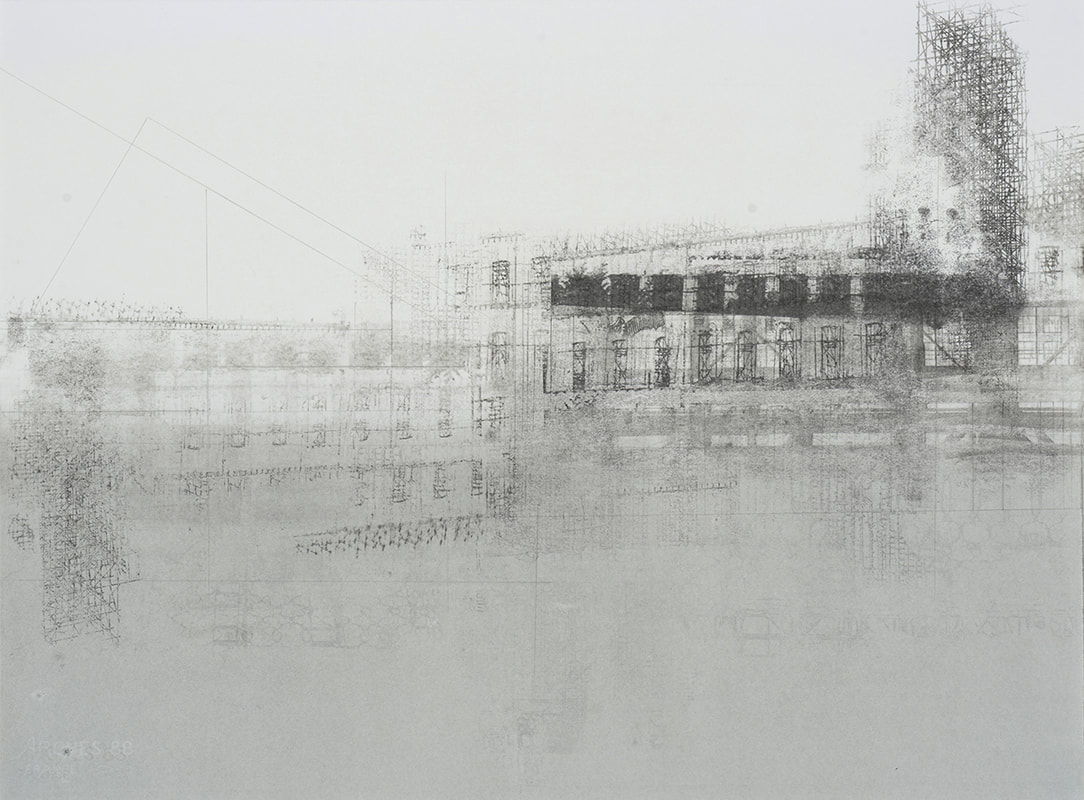

Landscape in Transition

Landscape in Transition

ITALIAN SCENE

Jeffery Beam

It is through celebration that we become part of what we perceive; the great arc of birdsong — that runs around the world in the receding darkness & through which we are swept into the light of day — is as much part of the dawn as the sun’s first flash.

—Norman Mommens

Morning swifts piercing rippled clouds their circling narrows a blue tower Cypresses between vineyards hillsides hung with goats & stormlight

Villas in rain figs marrying the vine

Perpendicular cliff footpath to cave rosemary midnight crevice

Pick up stone surprise eternal weightlessness how heavy Straw whispers Goddess’s cold breath

Then falling water lemony smoke warm breezes

Pick up stone surprise eternal density how light

We pass a red blaze roasted pears honey wine Under deepening sky a hundred candles in windows Simple rapture woman crouching in the garden

IN LUCCA

Sweet angel, little Italian boy,

whose voice rises with his mother’s

in the afternoon light and the old woman crooning to her cat in the courtyard’s shadow,

the pigeons’ cooing, the piano

melancholy from an upstairs room,

this beautiful sameness greeting us each afternoon as the day descends in the churches,

in the old town, and the Madonna,

San Sebastiano, San Michele,

flutter above the roof tiles,

their haloes, arrows, wings

trembling secretly, phrases

repeating over and over by the child,

and the room settling into soothing monotony, and the sunset, and the sweet angel Italian child waiting

impatiently for his supper to come.

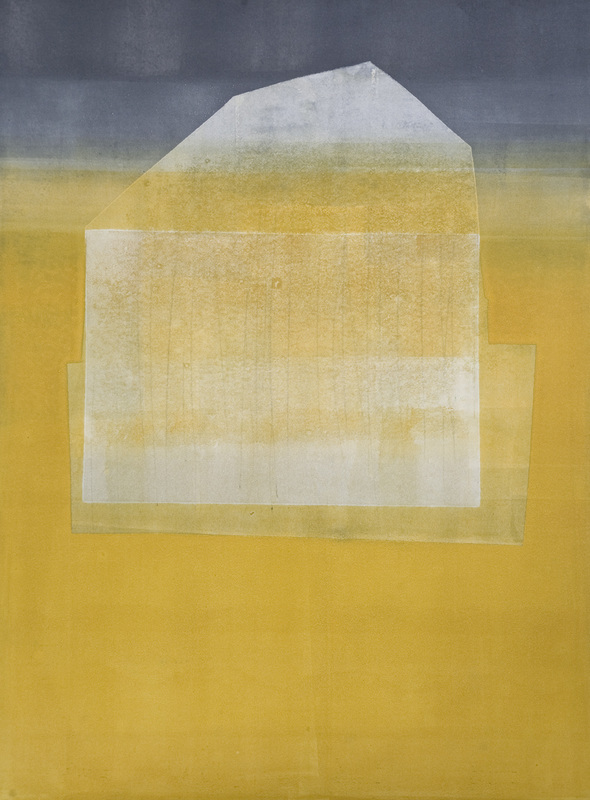

Color Field

FLORENCE IN ECSTASY

AN EXCERPT

Jessie Chaffee

Following signs that lead me through the original walls, I walk into the old center of Siena. It’s early afternoon, the church services are over, and the shop windows are dark. Only the occasional coffee bar is open, the interior a cool rectangle broken by no more than one or two bodies gripping espresso and glancing up at a small television. Soccer.

The streets are tighter than Florence’s and the buildings on either side too close to me, slicing the sky into narrow strips. Siena is an older generation, cloistered and closed, and I feel trapped with nowhere to look but up at the church towers or down at my feet. Medieval. So this is what it means. Tunneling between buildings, I find my way to the only open space, the Piazza del Campo, a cobbled Tilt-A-Whirl of a square edged in cafés. I visit the unfinished duomo, then drift to the edge of town, to a church balanced high on one of Siena’s hills. It is massive but plain, and a worn wooden door on its side is almost unnoticeable. The door is open a crack, and I enter to find a similarly sparse interior, cool and hushed. I like the simplicity of this space—the walls are light stone, the ceiling wooden beams. I would like to stay here to read and write and think. I would like to stay here to wait for answers. I breathe out and then in and catch the scent of incense. Halfway up the nave a woman kneels by a side chapel, but otherwise the basilica is empty.

As soon as I take a few steps, however, a priest appears. He is small and old with tufts of white hair around his ears. He squints at me, smiling, his lips folding into his face, and offers me a tour.

“Grazie,” I say, and then realize my error. He begins speaking rapidly in Italian but with such excitement that I don’t stop him. He takes the edge of my sleeve and leads me to the back of the church, to a small fresco.

“Conosce Santa Caterina?” he asks.

I nod. Catherine of Siena. I studied her in college—or paintings of her, anyway, and this one is familiar. She wears a black-and-white habit and holds a stalk of lilies. It is pre-Renaissance—her features are flat, her almond eyes lowered without expression, the proportions slightly off, and she has a greenish glow. Eerie. On each of her hands sits a drop of blood, the stigmata. What else? She had visions and ecstasies like St. Teresa, I think. And she claimed that she had married Jesus in a dream.

We stand for a moment longer, the priest gazing up at the portrait and shaking his head. He looks close to tears. Then he takes the edge of my sleeve again and we are off—he speaking and I not understanding, his feet shuffling along the marble floor with a shhh, shhh, shhh, and I try to step more lightly. He walks me up the left side of the church, stops at several paintings along the way, gestures to the ceilings and I catch a series of dates. When we get to the front of the cathedral, he points to each of the stained-glass windows, naming them. Then he leads me to a chapel that is frescoed on three sides. At its center is a small ornate shrine, a mini- cathedral.

“Questa è la sua testa,” he says gravely.

“Her head?” I ask.

“Sì, her head,” he confirms.

Indeed, within the shrine is St. Catherine’s mummified head

shrinking into a crisp white habit. The cheeks are sunken, the nose almost gone, the upper teeth visible, the eyes closed but the eyebrows seemingly raised. I look around to see if there are any children who might be traumatized by this medieval mummy, but it’s only me and the priest and St. Catherine now.

“E anche il suo dito.” He gestures to a glass case off to the side where a single finger, crooked, points heavenward.

“Her finger?”

He nods happily and points upward, too. He keeps smiling—this must be the end of the tour. He shakes his head when I offer him money but gestures with great enthusiasm to the frescoed walls of the chapel and bows slightly before disappearing.

I leave the dismembered saint to herself and look at the frescoes, which piece together Catherine’s life. These images are more relatable. They must have been painted a century or more after she died. They have perspective and expression, and instead of a blank background, Catherine is out in the city, architecture and landscape behind her. In one image she is collapsed, receiving the stigmata. She looks upward in ecstasy, her body not her own. On another wall, she prays for a man’s soul as he is executed. His head, like hers, has been torn from its body.

The third fresco stops me short. St. Catherine, right hand raised, stands over a young woman possessed by demons. A crowd has formed, but the people peer at her from behind pillars or hide their faces, shrinking back from the scene. Cowards. Only St. Catherine is calm, her eyes down, her raised hand unmoving. The possessed woman writhes on the ground beneath her, her arms straining up at unnatural angles, her head thrown back.

Which of these women am I? The one straining madly toward something unseen, or the calm one looking on? I have been both. In this past year, I have been both. I have been the madwoman screaming, straining, digging ditches around the bone. Sculpting.

When did this start?—my sister’s voice, a flat note as she watched me disappear. And still I could not stop digging, could not stop sculpting. I would be well sculpted. But I was not mad. I was calm. She couldn’t see. She couldn’t see that I was not only taking away. I was reaching for something. I was creating.

I stand for what must be a long time in the little chapel in front of this fresco. Catherine’s face belies nothing as she gazes at the possessed woman, but even the saint, I decide, was more than her patient reserve. I look at the first painting of Catherine in ecstasy and then back to the image of this writhing woman. They seem the same, and I wonder if, in looking at this madwoman, St. Catherine recognized herself, frozen in one of her ecstasies, envisioning. Of course, she had been told that the woman was inhabited by an evil being, not God. Still, it seems to me that Catherine is looking in a mirror, and I wonder if she realized this and if it struck her as odd that she had been asked to heal her own reflection.

I stop in a gift shop, the only place open, and find a book on the saint’s life. But as the train pulls out of the city at dusk, I can’t focus on the words. I put the book on the seat beside me and close my eyes.

I see myself already back in Florence. For a moment I am in two places at once. It is always this way when you travel. You exist in two places at once, as two people at once. There is the place you are now and the imagined place you are going, where you are already wandering streets, having dinner, strolling back to your hotel. There is the you that is here and the future you already there, smiling and confident. And that future place is not a busy intersection in Florence at night, or a darkened alley where words chase me. It is not the place I feel I am perched, always precariously perched, these days. The future place is better and in it is a better me. Not the me riding lonely on a train, running from everything I knew and everything I was, but the me that is knowing, flirtatious, unfettered, savvy, healed. The thought is reassuring, but then it turns and is terrifying. That future woman is not me and I know how she will look at me, the past her. I know how she will pity, patronize, want to expunge, destroy. She will say, I remember what I was, before I learned. She will want to erase what is mine. But this is me and this is mine. This lonely train ride is mine, too.

Out the window is a parade of shadows and I am a single point in the dark, one lit window passing by. This is the first day, I think, looking out at the darkness and seeing suddenly my own face. This is the first day of the rest of your. The rest of your. The rest. This is the first day. This is the first. The rest. Your life. Then: The rest of your life. What if this is the rest of your life?

But this is the place where I am: on a train in the dark. And, in truth, the place that I’m going doesn’t exist. She does not yet exist.

´

Double-Lifers

Lyall Harris

BANDWIDTH

From Chaffee’s Florence in Ecstasy excerpt: For a moment I am in two places at once. It is always this way when you travel. You exist in two places at once, as two people at once. There is the place you are now and the imagined place you are going… These lines ring true not just for those who travel but for those who cultivate lives in more than one place, which is often the case for expats in Florence. A double life always implies distance from one of the lives—some things will be missed or left unknown, or we will arrive too late, but the double life also often includes an intensity of experience in the current life for the very same reasons: because you were there—for a long afternoon with a cherished friend (all the more cherished because you know how rare she is, having never met anyone like her in your other life) or to see the newborn baby (and his exhausted but beautiful mother) or to light a candle in San Miniato for your beloved father-in-law while a storm brewed, clouds the color of Carrara marble veining blotting out Brunelleschi’s dome. Because you were fully there, these events are inscribed into you.

Double-lifers know a thing or two about coming and going, about joyous hellos and tearful good-byes, about packing up one life and unpacking for another. In the in-between, they are, as Chaffee says, two people at once, and it is perhaps only in this liminal space that the lives overlap and merge, that they sift together, and the double-lifer finds herself strangely whole and vibrantly alive.

?

What impression do you leave behind?

LANDSCAPE IN TRANSITION

ISSUE 18 • Autumn 2018 will be published in September.

Visit www.thesighpress.com for details.

© 2018 THE SIGH PRESS

None of the work published by The Sigh Press may be copied

for purposes other than reviews without the author and artist’s written permission.