Notes from The Sigh Press Editors

Mundy Walsh & Lyall Harris

The tempting body caging the ghost was leaving a world which loves to forget.

Contents

*

[ ]

[ ]

,

´

?

*

OAK

[ ]

DERECHO

Elizabeth Logan Harris

I travel on the heels of a massive storm. Below Culpepper, the train rolls through darkened country, stopping at every junction so the engineers can signal by hand. When the train finally pulls into Lynchburg, I wander down the dim platform amid the disoriented throng. I strain for a familiar face in the headlights of the waiting cars.

It’s a hot July night and I’m sweating by the time I see my father’s stork legs against the moonlit cement. His cane is only a little thicker than his calves. Happy Birthday, he says with open arms. I’ve just made fifty. He leads me to the car. My mother is behind the wheel, the engine is running, the AC full blast. Enjoy it while you can, she says of the car’s cool cocoon. Who knows how long the power’ll be out? Some parts of Lynchburg—the outskirts near the mall and the airport—still have power. But all of old Lynchburg is dark. And we hale from old Lynchburg. Behind the train depot my mother turns down the cobblestone lane. The storefronts in shadow, the street has a spooky, desolate vibe. My mother slows at a useless streetlight. She indicates our usual route home. Four trees down in that direction. My father gives a backward nod. The way home by the high school is blocked, too, he says. The only clear route is down Hollins Mill Road where the drive-in used to be. I miss the drive-in, my mother says. There’s a word for the storm, she adds. A Durango? she says. Or no, maybe—what was it Katie said they called it? I thought she said, Chericho, offers my father. But for the dark, my mother and I might exchange a conspiratorial look in the rearview. Though it’s hardly necessary. She and I do not need to confirm our mutual doubts about my father’s interpretation. My father is notorious for his malaprops. He once introduced a university official as the Pro-Most. Whatever the name of this storm turns out to be, I’m glad to hear my father contributing to the conversation. He recently plunged back into the depression that has dogged him for years. And he plunged with a vengeance. Some days he lies in bed till afternoon. The storm was enormous, an unusual weather system that cut a seven-hundred-mile swath from Fort Wayne to Annapolis. Lynchburg has some of the worst damage in the state. It blew up, just like that, my father says as we swoop down the big dip past the Hollins Mill waterfall. You never saw anything like it. I squint into the darkness, into the wooded berms and yards of old Lynchburg. I see enormous trees and limbs bestriding lawns and streets. It’s just as my mother has described. Roof after roof is crushed. Garages pierced, vehicles flattened. Powers lines loose, dangling from branches. Some hang in low swags like bunting for a sinister parade. We pull into our driveway. As the headlights sweep across the yard, I see our once-mighty oak, the hard heavy fact of its giant trunk just inches from our three-story stucco. Twenty-one and one half inches, my mother says. That’s how close it came. I measured. We pick our way around its top branches. Watch your step now, my father says, his flashlight bobbing as he speaks. It did chip a corner off the roof, my father says. This house on the Avenue has been in our family for seven generations and entering the house after not being home for a while is to enter a chamber of childhoods, not only mine and my mother’s, but her mother’s before her. My father lurches up the stairs behind me. He wants to have another look at our damage from the upper story. We enter the guest bedroom. It is stifling. Out of the room’s six windows, two are open. These are the only two screened windows in the whole house. My mother has told me as much downstairs. My father shines his flashlight out the windows where an enormous bough is pressed against the back windows. The branch broke off the sweet gum and fell onto the roof of the back porch during the storm. We are lucky the whole tree didn’t fall, he says. Looking out the window, I realize that what little breeze might ruffle through the night will have to pass through this leafy protrusion before it gets to me. No more screens? Really? I ask. The storm windows are still in, he says. The screens are still in the storeroom. The storeroom is around the back of the house, dark and buggy under the best of circumstances. I can tell from the aggrieved look on my father’s face that we will not be going there tonight. He would want to supervise it. And since he doesn’t have the balance or the stamina to do so, he would stand there getting crabby, worrying whether we were doing it right. It’s not a big deal, I say. I raise another window. I wouldn’t if I were you, he says. We tried that last night in our room. The skeeters ate us up. Finally went to the basement, slept on the sofa bed. It’s ten degrees cooler down there. Wouldn’t believe what a difference that makes. I hear my father but having lifted the window, I set about trying to lift the storm pane. I lift it but it won’t click in place; the latches are sprung. It falls down. I look around for a book, anything to prop it open. Sweat runnels down my face. I hear my mother coming into the room. With just us in the house, your father didn’t think it was necessary to take out the storm windows this year, she says. I let the window drop. I turn to find my mother standing in the doorway with a blazing candelabra. She gives me that he-wanted-to-save- money look. By the light of five tapers my mother’s exhaustion is apparent. Her narrow face seems to have narrowed further, her small features withered, her fine hair, absent its usual blow-dried umph, clings limply to her head. And yet she is rising to this crisis as she has risen to so many others and I recall the kinetic black-haired beauty who raised me: art historian, gourmet cook, passer of the Episcopal chalice, member of the book club and the quilting circle. Here she is, come to meet catastrophe with equanimity and family silver. By the same light, I see the strain on my father’s face. His shoulders hunched to his ears, his full lips pursed with effort, his gaze fierce and distant as he stares down some inner ghoul.[ ]

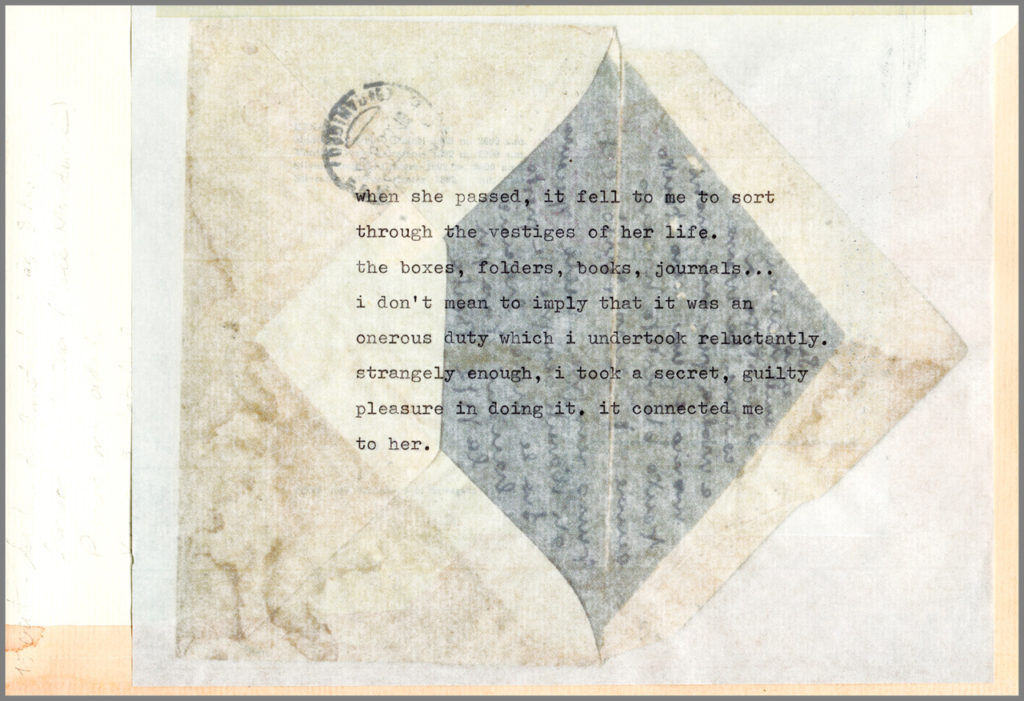

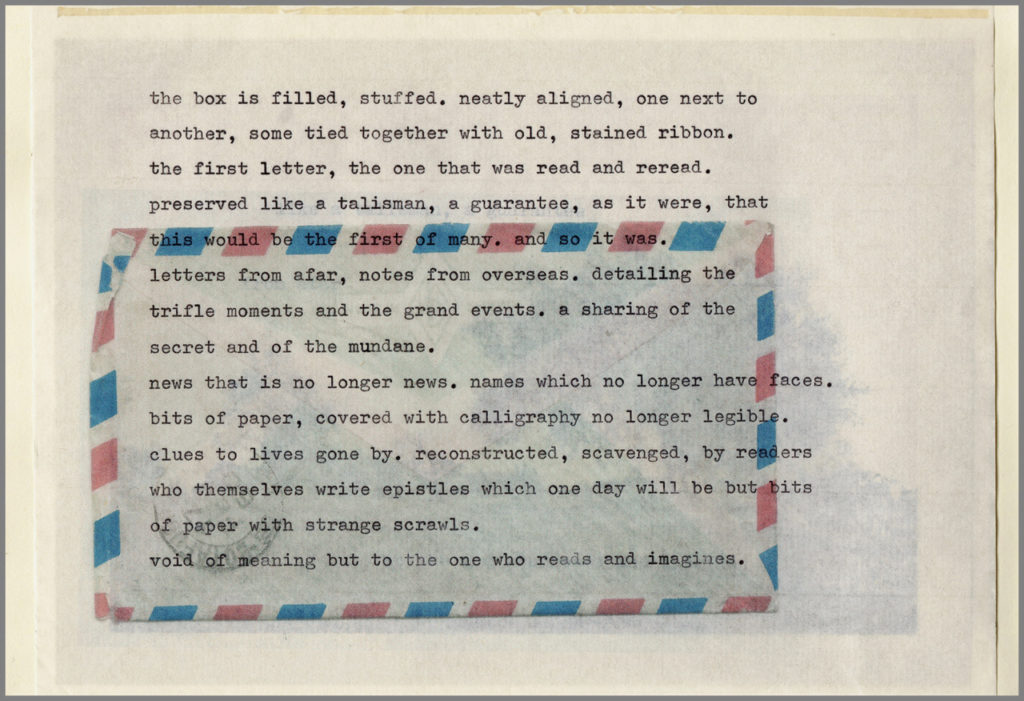

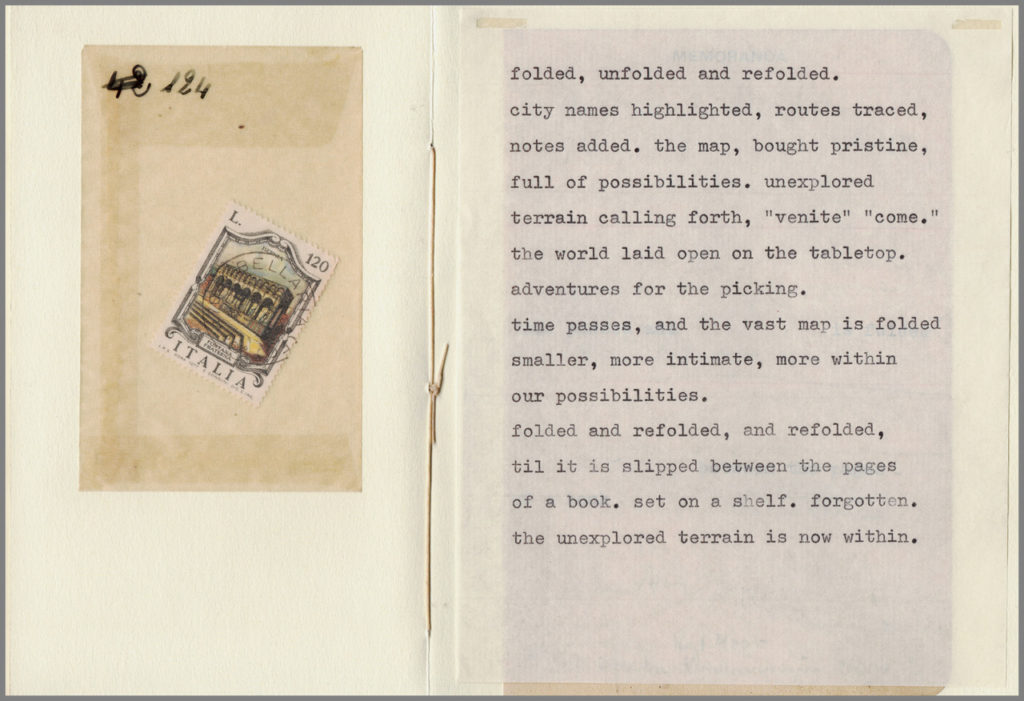

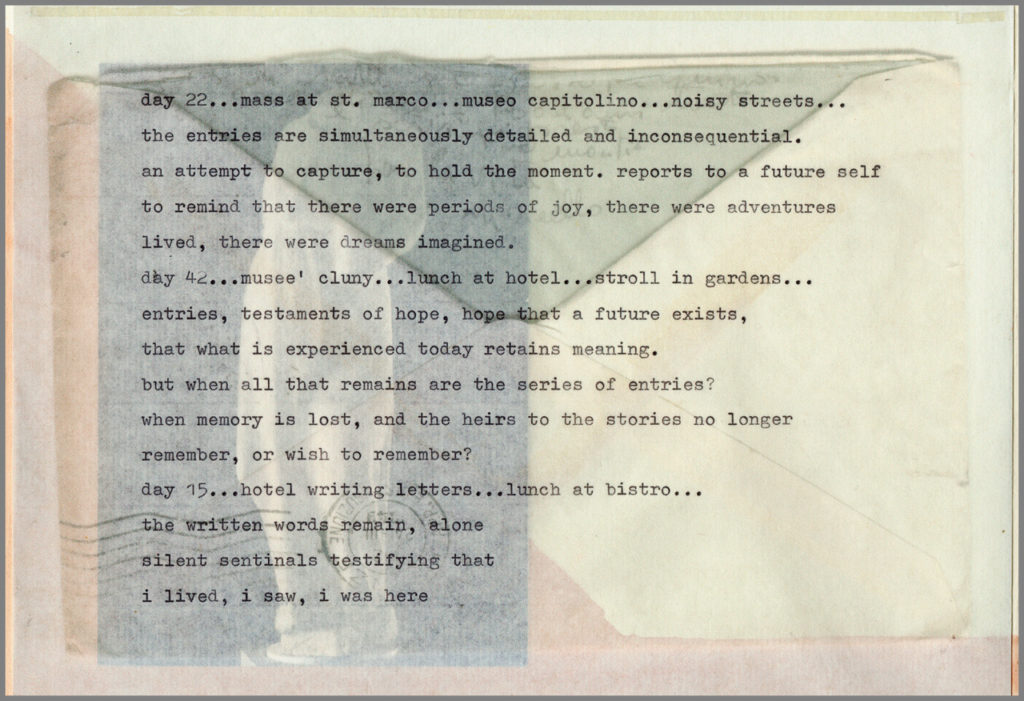

NOTES FROM OVERSEAS

Patricia Silva

,

GRANDMA

Sonnet Mondal

The flowers are moving. She must have whispered something to them! The waters are murmuring She must have shown them a path! I lie on my knees mystified beside her bed waiting for her to speak and deliver me from my despair. Wrinkled skin pressed against the edge of an old cot hangs out to touch my forehead. GrandMa is not dead. Her spirit is. I am being killed by her ennui and her feeble longing to work again. Neither am I dying nor her languor. Reflections as skipping stones are leaping over my melancholy. Why do I feel my years getting locked in a second?

WHEN YOU LEFT

ANSWER MAA

I still sense your presence around that door but a sound from this opening seems like an echo in the wilderness — warning as well as bewitching me to reveal myself to the untraveled. Still for my senses, like a deserted impala calf — I am hurling questions and calls to the woods drowsy in meditation. Maa, I know you won’t answer. I am therefore standing soaking myself trying to find answers in the undertone of this rain falling on the tin house. In a skirmish with anxiety I am awake — waiting to meet sleep in person: if she has heard you somewhere Answer Maa Or what’s the purpose of perpetuating the thirst of my eyes? Tears are digging deep inside. A canyon of remembrances is getting drilled. Answer Maa

WHEN YOU LEFT (II)

BEGINNINGS

When I read a book of poems I try to think of the moment when the first flow of thoughts gushed through its pages. When I hear a music album I try to think of the moment when the first note of the first track in it kissed the muse of its roots. When I walk barefoot, pressing ageless soils and gravels — I try to think of the moment when the earth was reared from ashes. But, never do they recite the first anecdote of the planet. My head like a shapeless asteroid revolves around beginnings — to peer inside the static stance of time and the state of mind that sets it in motion.

TOMORROW

IN FRONT OF A BURNING CORPSE

A corpse was burning in the burning ghat by the sea. A dog was looking at me and whimpering. Amid the flaming sounds and laughter of waves the sea seemed to be in a gossip with the skies and the burning corpse looked like an ignited cigar — smoked by the rolling drunk waters. I felt like an infant ghost watching at its birth. The tempting body caging the ghost was leaving a world which loves to forget. Breathing seemed as trivial as the cries of the dog and life was no longer a doubt. The roaring clouds above were like memories warning of its presence to the transforming soul. The flickering sodium lights were trying to lighten the worth of loving and leaving. All that was spoken and done floated like vain lies over untiring waves. I felt I was someone else and while battling to become that someone else I lost myself like a trifling dot in the infinity.

1863

DADAJI

The birds were returning home in the backdrop of an amber sky. Some kites were circling above their newly-built eyries. My house has always been a landmark for whom the whole sky was one path. Watching them yesterday from a caged balcony — I was thinking of my dadaji. His image clear enough to lead me through forests through stories surprises. I had a strange joy in my infancy sitting in hutments with him throughout the harvest overlooking lush paddies awaiting the clean sunny smell of stacked hay. Today morning dadaji visited me uninformed. Leaving the doorstep he held me by my shoulders — you aren’t that little child anymore you won’t come running behind… I stood bidding adieu. He smiled still aesthetic in his nineties. Above — birds flew in an ultramarine sky to start their day. We are the same but our priorities have shifted their course. Dadaji- Grandfather in Hindi´

LEGACIES

Charles Halsted

On a clinic visit she confided to me her ancestral African slavery, her people brought below decks in terrible chains to Trinidad to labor for generations for a succession of Spanish, British, French, and Dutch plantation owners. Freed in 1833 by British abolition, slaves continued to work as indentured servants, growing and harvesting the principal crop of sugar cane, which could be converted into coveted rum. In the next leg of triangular trade, rum was exported to the United States and back to Britain. Coincidentally, in 1826 my fourth-generation forebear established the family fortune in a textile mill on the Merrimack in New England where children were paid in pennies to make clothing out of cotton, the slave-dependent Southern crop decades before emancipation. Rum slaked the thirsts of the ruling class, the New England aristocracy, whose fortunes were made on the backs of these children, and on the backs of African slaves and former slaves toiling in southern cotton fields and in cane fields under West Indian sun.?

Who feels the reverberation of Rosalie?

ROSALIE

ISSUE 23 • Winter 2019 will be published in December.

Visit www.thesighpress.com for details.

© 2019 THE SIGH PRESS

None of the work published by The Sigh Press may be copied for purposes other than reviews without the author and artist’s written permission.