Note from the Editors

Lyall Harris & Mundy Walsh

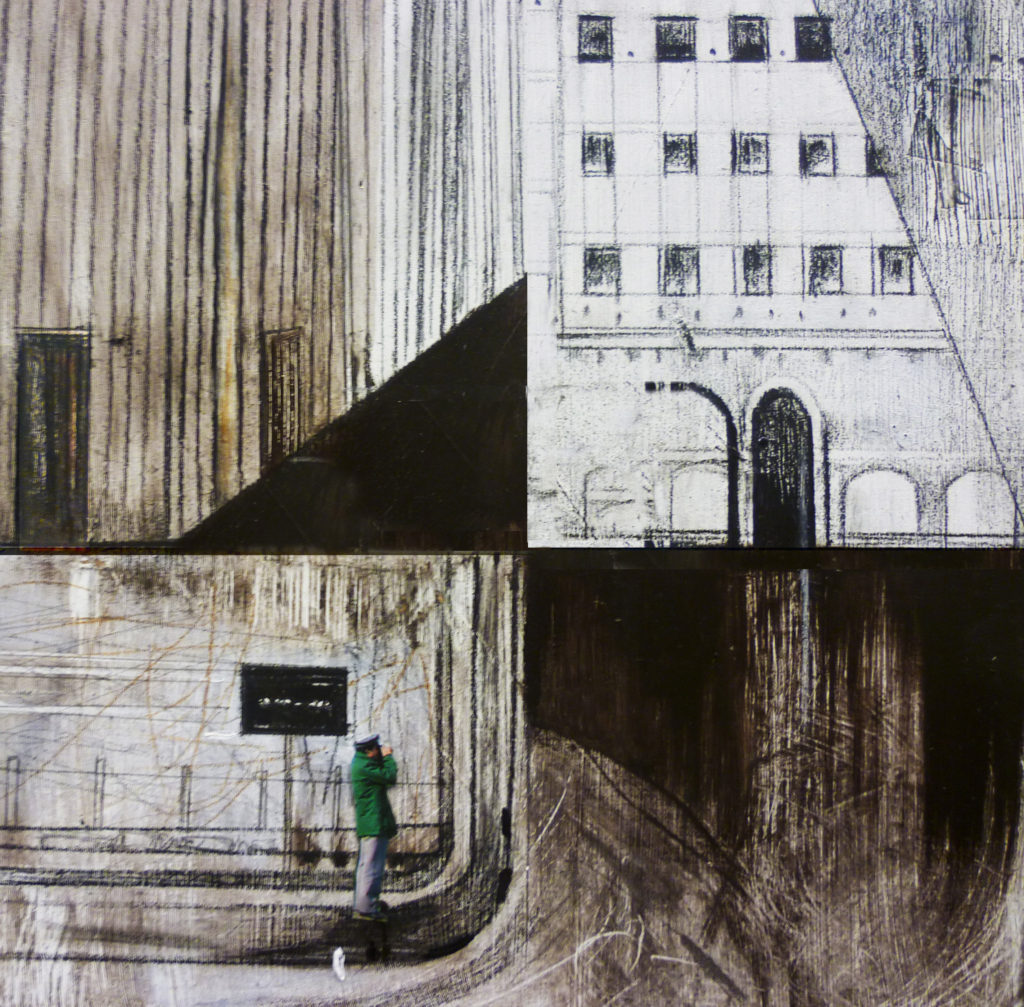

The heat has lifted and the rains are coming. In fact, they are coming right in through the roof in Shivaree, a new story this issue by Isabella Ronchetti. You’ll find all kinds of “architecture” in the fall journal. Our current theme—“Inner Architecture”—was largely inspired by the work of visual artist Ilaria Leganza whom we met at the Stibbert Garden Art in the Park event , co-sponsored last spring by The Sigh Press. From Jessie Chaffee’s musings in Autumn Window to Brenda Porster’s take on a “curve,” all of the work in this issue addresses the theme in different and unusual ways. And, as always, contributors’ bios and more can be found at the end of the journal.

After our standing-room-only poetry event in the spring, The Sigh Press will again partner with Florence Writers on October 22nd to host an Open Mic Poetry Night at the St. Mark’s Cultural Association. Writers are invited to sign in when they get there, grab a Negroni on the house, and participate in the local poetry scene.

The previous weekend, on October 17th, editor Lyall Harris and Sigh Press contributor Elisa Biagini will hold a poetry and book art workshop.

You can now find Sinéad Bevan’s winning story My Big Fat Modelling Career also in audio format (see Quotes page for all podcasts), read by the author. Sinéad’s funny, poignant story was The Sigh Press winning entry in the spring short story competition held with The Florentine.

Please visit Submissions for our Winter Issue theme and deadline, and don’t miss us on Facebook where you’ll find the details about events, Sinéad’s reading, and more. Check out the pdf version of The journal.

Subscribe to our newsletter, where you’ll receive the latest issues, Ampersand interviews and news:

Contents

*

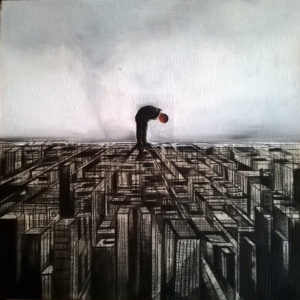

ARTWORK, Ilaria Leganza

–

( )

!

–

´

?

MILLIONI DI MILLIONI

—

THE CURVE OF THINGS

BRENDA PORSTER

SI SALE O SI SCENDE

“These things do tend to take a certain curve” –

so what do you do at the end of the curve?

get off, I suppose, or, better, are let off,

stepping down to a point off the line,

a bleached and empty landscape, displaced

you look around you and can find

no horizon, no axis to refer to, only

vast suspensions of space

and time with no direction to follow,

except backwards,

where you cannot, will not go

though your body’s every fiber

be aligned

to that pull.

[ ]

AUTUMN WINDOW

JESSIE CHAFFEE

I am a visitor to this view out the window of the kitchen where I sit each day. I write here because of the view, the depth of it—the stacked homes and scalloped roofs, the single cypress, the far-off hills, and then sky, sky, sky, all reflected in the two glass panes that open toward me like hands, dripping with reflections. In the distance, planes drift down and shoot up, sharp arrows, as tourists come and go through September and October and now into November, though it doesn’t feel like November, the air still warm, the only sign of autumn the early-setting sun and the fire-red vines that hang from a terrace halfway between me and the horizon.

With the window open, sounds cut cleanly to me. The shrieks of birds, the slicing of stone, the couple shouting in the apartment below— their voices crescendo as though this battle, repeated each day, might be their last. It has rained for weeks, pulling smells from the crevices, polishing the roof tiles, and slickening the slotted stones. But now the sky is clear, a momentary break, as I look out to the soft melancholy of evening where a woman is slowly drawing in her laundry. I turn away, disappear into words, tap tap tap at my keyboard, pausing only at the bells to turn back to this view, to the fast-approaching dark, to remember where and who I am.

Donna Volante

!

SHIVAREE

ISABELLA RONCHETTI

My parents’ voices made the sky parlor cave in so lamps hung from clouds and rain ruined rocking chairs and napkins.

No one heard me let the Soulstealers in through the bathroom window, no one heard the whirr and hum of their bustling thoughts spread through the house, whispers faint as wolf’s groans swallowed by vapor. They clogged every gap and crevice and those that didn’t have room began a blind shivaree of kettles and wooden spoons in the kitchen, darkness leaking in through cracks in the walls.

They crawled into the sitting room and tore upholstery with their sharp teeth and claws, begetting billows of down that drifted through the rooms and settled in forgotten corners. Letting fly feather-confetti, they capered through the corridors and cachinnated and crooned.

“Come and play,” they sang, “Come and play.”

Their hymns and canticles were in a tongue only I could fathom, a tongue of yearning, of vengeance, of thirst.

Then they called to the others, who gathered round that bathroom skylight and pushed and fought to get in first. They broke mirrors and disarranged my closet of dresses and costumes and masks; then they held hands and climbed up the walls, juggling knives and ceramic apricots.

And they brought in more darkness that trailed behind them as they skipped through the house and lit fires under the beds.

My parents’ voices droned still, oblivious to the Soulstealers and their frenzied jubilee, to the spreading caliginosity and the crumbled garret.

“Come and play,” they sang, “Come and play.” And the rug grew wetter still as the nimbostratus layer continued to cry through the hole in the roof.

I wasn’t afraid of my soul getting stolen: I’d already lost it anyway.

RICORDI

!

THE CORNERS

ISABELLA RONCHETTI

Five empty slots in the box where the cookies should be, five empty corners in me where my guts, femur, vocal cords, carotid glands, heart once were.

Those two cats that stole them used to cry in the night and I remember lying there, listening. They sounded like human babies. I remember lying there, listening, and feeling the pulse of my bed’s young heart and the faint vibration of my sofa’s tired, tired vocal cords.

When I was little I was given a pocketknife and made a small slit in my grandmother’s upholstered chair just to watch the intestines squirm out. No blood; back then I didn’t understand why. The intestines slid to the floor and more kept coming, oozing through the thin cut I’d made and forming a puddle that little by little expanded and grazed the fringe of her Persian carpet. So I sewed the thick floral skin back together with black thread and burnt the guts that had leaked out, afraid she might be angry about her ruined rug.

Once, grandmother brought me five vanilla cookies on a paper plate as I sat on a frail yellow beach chair by the pool, neglecting the rattle of its weakened bones. It was that very afternoon, while I was observing a family of wind-up cardinals nest in huckleberry bushes, that my femur was

taken by those retched cats. I raided the closets and searched through her entire collection of umbrellas; I persevered until, months later, I was not only searching for my femur but also for my stolen carotid glands and guts.

It was years before I lost my vocal cords, then my heart. So long a time passed, in fact, that I almost believed the cats had given up. I was living in an aluminum tree house with a wooden bed, breeding wind-up birds. And they stole my vocal cords first so I wouldn’t be able to call for help when they took my heart.

No one has ever noticed the five empty corners in me, like the slots in the box of my grandmother’s cookies.

LA STANZA PROIBITA

—

TWO SKETCHES FROM TROY

NICHOLAS CHAPMAN

Criseyde

Her beauty, so bright as to blank our gaze,

Empties the room.

In her presence we know ourselves most

Ordinary. She stands apart, is left alone.

A widow – with no child – and now a traitor’s daughter.

She knows what this means for her.

This is a small town.

Troilus

Young soldiers – who’ve seen a thing or two

These past seven years – swirl down the street.

It’s a feast day, and here comes the sun

Lifting her skirt above her ankles. A little heat

And the fuse is lit. Except in him.

He judges some fair enough, some wanting

And does not burn in the taking or the leaving.

Avvistamento

´

LIFE IN THE BALANCE

JASON ARKLES

LA MIA CITTÀ

As any sculptor will tell you, the human figure is fundamentally unfit to be rendered in marble. This, despite several thousand years of trying; and the problem is one of architecture. Even the slenderest of torsos are too massive to be carried by the thin forelegs and ankles of the human body, when cut into stone. Ankles will crack and the marble figure will topple unless some artifice is added to the art. And so Michelangelo’s David gets his tree trunk, Venuses employ carved draperies or urns, Hercules his club and lion’s skin. But find the correct balance of the figure by use of this third leg, and your figure will stand the tests of gravity as well as time. It will stand, and your subject has become immortalized.

The third leg is just one artifice we employ to create an illusion of reality. Cavities in the eyeballs give the effect of a colored iris, hair is treated in terms of its general mass rather than a collection of individual wisps. And we use these conceits in figurative sculpture of every medium—bronze, wood, and clay as well as marble and stone. But it is marble and stone alone, the most permanent, unmoving, monolithic (in its literal and figurative sense) material which requires of us the greatest concession, the third leg, before the immortal nature of the medium is imparted to those who would seek it.

Of course, this so-called immortality is also a conceit. Artists and their muses must die, and what is left behind is only an effigy. I like to think of marble and stone statues as wanting to break; as needing to leave the legacy of impermanence as much as immortality; reminding the artists that, if we seek Truth and Nature in our work, then maybe our work must die too.

?

What names do we give the familiar yet invented places in our dreams?

LA TORRE DEI SOGNI

ISSUE 7 • WINTER 2015 will be published in December.

Visit www.thesighpress.com for details.

© 2015 THE SIGH PRESS

None of the work published by The Sigh Press may be copied

for purposes other than reviews without the author and artist’s written permission.