Welcome to another interview in the Ampersand series: interviews with writers from all over the world who have a connection to Tuscany.

We are pleased to announce our seventh Ampersand Interview with Iranian journalist and narrative nonfiction writer Kamin Mohammadi. A Tuscan transplant from her other adopted home of London, Mohammadi positions Italy and Italians front and center in her forthcoming book Bella Figura; How to Live, Love and Eat The Italian Way (Bloomsbury, 2018).

In the upcoming December issue of the journal, we are already looking forward to Mohammadi’s personal and layered story, Biological Clock, in which she discovers that what seems lost might not really be missing.

In this interview, in addition to learning about her relationship with her craft, you’ll glimpse some of Mohammadi’s life story and early hardships—and yet her optimism and joie de vivre also permeate the pages.

Subscribe to our newsletter, where you’ll receive the latest issues, Ampersand interviews and news:

Ampersand 7 – Kamin Mohammadi

Kamin Mohammadi is an author, journalist, broadcaster and public speaker. Born in Iran, she and her family moved to the UK during the 1979 Iranian Revolution. As a journalist she has written for the British and international press including The Times, the Financial Times, Harpers Bazaar, Marie Claire, Condé Nast Traveller (UK and Italy), Psychologies, Donna Moderna (Italy), Grazia (Italy), Men’s Health, The Sunday Times (UK), The Sunday Times of India, The Mail on Sunday, Virginia Quarterly Review and the Guardian as well as co-authoring The Lonely Planet Guide to Iran and numerous other travel guide books. Her journalism has been nominated for an Amnesty Human Rights in Journalism award in the UK, and for a National Magazine Award by the American Society of Magazine Editors in the US.

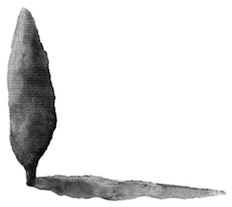

Kamin has also authored a book, The Cypress Tree: A Love Letter to Iran (Bloomsbury, 2011) which was published in Italy as Mille farfalle nel sole (Piemme Voci, Sept 2013). She has recently contributed an essay to the Italian anthology: Pensiero madre (Neo Edizione, June 2016). She has spoken on Iranian issues at universities, conferences and peace events, including at New York University in Manhattan, a briefing to NGOs, lobbyists and senators on Capitol Hill, the London University Union as well as for CND in the UK. She has appeared at various literary festivals around the world including the Jaipur Literature Festival 2012, the Bath Literary Festival and the Oxford Literature Festival, as well as Asia House London’s Festival of Asian Literature twice. An avid commentator, she has appeared on BBC Radio Four’s Woman’s Hour, Midweek, Four Thought and The World Tonight, BBC World Service’s Outlook and The World Today Weekend, Channel Four Radio’s The Morning Report, Monocle Radio’s Monocle 24 and India’s NDTV. She has appeared in the BBC (television) documentary Iranian Enough? and helped to write and co-present the BBC World Service’s three-part radio documentary Children of The Revolution. She was a major contributor to the BBC Radio Four series Escape from Tehran. She is now the regular presenter of BBC R4’s Four Thought.

What book (not written by you) comes closest to capturing something about you? What is this aspect?

I guess the obvious one is Persepolis by Marjane Satrapi – the excellent graphic novel about the Iranian revolution, the first one specifically. Although our experiences differed in their detail, essentially they are the same (we even attended the same school in Tehran as children). It was the first time that something of not just the tragedy, but the hilarity and absurdity of living through the revolution was captured for me with such innocence and verve, an antidote to the ‘misery memoirs’ that had been the norm in writing about the revolution. It inspired me to also make sure to weave the beauty, magic, love, resilience and humour of life in Iran in my book – something of a challenge as I am sorry to say publishers often like the misery genre better with its sensationalized accounts! I have to thank Bloomsbury for allowing me to write The Cypress Tree my way and also disclose that the above reason is exactly why my book didn’t find a publisher in the US – as I was told by editor after editor who said they loved the writing but without more violence and sensation, there was no market in America! Italy too embraced the quiet storytelling of The Cypress Tree (called Mille Farfalle Nel Sole here) – thank you Piemme!

What is the biggest personal obstacle you must overcome in order to write?

Procrastination! I have been known to wash carpets, clean windows, even move countries in order to put off writing. Although as I gain more experience, I realize that the procrastination is, curiously enough, a part of the process. So I try not to beat myself up too much as that’s the real problem – the self-hate that comes with putting off writing. Sometimes it is the desire to escape from hating myself that makes me then write – so it kind of works and I try not to get too emotional about it all now.

After journalism, when and how did you know that memoir would become a primary genre for you? In your poignant book, The Cypress Tree, about your childhood in Iran and your family being forced to leave that country, what were some of the challenging aspects and/or unexpected rewards for you of writing in this genre?

I never chose memoir. I tried to write The Cypress Tree as a fiction but it didn’t work. My agent kept suggesting that I write it as a memoir and I kept refusing. Then, after about a year of me working on it as a novel (horrible stuff!) she said it again – and this time, the seed fell on fertile ground. I tried it and it flowed and that’s how memoir chose me.

In my journalism I always like to tell stories through personal experience. Again this was never decided or calculated – it’s just how I connect with a story’s emotional truth. One day a friend who was a Nieman Fellow at Harvard Journalism School, rang to tell me that there was a name for the type of features that I had naturally been writing – narrative journalism.

Because I think there is a bit of snobbery in the publishing world around the word memoir, I like to call my work narrative nonfiction. It feels closer to the truth of what I have done in both The Cypress Tree and my new book, Bella Figura, as they tell a story and read like fiction, rather than biography/autobiography. I guess my shyness about the word ‘memoir’ is thinking that it is all about me, whereas both books are about telling a larger story than my own and conveying a broader truth that involves more than just little me!

What is something few people know about you?

My true wish was always to be a singer. It still is really.

It has been said that artists pursue one question in different ways throughout their work. Would you say this is true of your writing? If so, what is your question?

A great artist in her 80s who I met while working on The Cypress Tree told me the above when I complained about having to cut so many characters and stories from the final draft. She assured me none of it would be wasted as, throughout my career, I would essentially always rework the same subject until I was somehow done with it.

I’ve seen this is true. The new book, Bella Figura, could not be further in subject matter from The Cypress Tree: the former is about Italy, food, and how the Italians live, the latter is about Iran, history, revolution and exile. And yet, I see now that Bella Figura is also about Iran, exile, identity, just more in the negative spaces rather than upfront. But it’s there and informs the narrative anyway.

I am not sure what exactly my question is but it certainly revolves around identity, immigration, exile and reconciling my Iranian past and self with my European present. It’s about finding the common spaces and building bridges between cultures.

You came to Florence from London years ago to house-sit. That was the beginning of a very long and deep relationship with the region. Clearly your latest book, Bella Figura; How to Live, Love and Eat The Italian Way is directly influenced by living part-time in Tuscany. Are there more hidden aspects of Tuscany’s influence on your writing, for example and in stark contrast, does the reality of the immigration crisis, felt deeply throughout Italy, impact your experience?

So I think that I felt instantly at home in Florence as it reminded me in so many ways of Iran. Especially in the pace of life and how it is governed by the seasons and enjoyment of sensuality. It felt less European and more Middle Eastern under the Renaissance gloss and refinement. I think living in Tuscany has made me more aware of the simple pleasures of living, and of course life in Italy forces one to be light and flexible – otherwise as a rule-following, queue-loving Brit you would go mad!

As a fast-paced Londoner, there is a lack of ambition I found in Florence that made it very conducive to writing long form. As a small but very splendid and preposterously beautiful town it offers just enough stimulation (I find total isolation counterproductive) and yet is quiet and gentle enough to allow all that beauty to soak in and marinade your brain and be expressed through words. Living in Florence that first year and subsequently in Tuscany has given me permission to be sensitive to beauty and that makes very fertile ground for creativity.

I love Italy, Tuscany in particular and the Tuscans/Florentines. However, as a Londoner I must say that I feel the lack of multi-ethnicity and openness to integration with other cultures keenly. It’s lovely that Florence is so mono-cultural (if that’s a word) as that is also its charm but this security in their place in the world can make some Florentines rather stagnant and provincial in thought and make for closed minds and an arrogant attitude which is quite misplaced I feel.

The new generation is changing, they are more open, I can see that, and I guess immigration is very new to Italy, and coming now in quite overwhelming waves, so I can also understand why people’s initial reaction might be to close ranks and push away The Other. But you know, I also believe in the essential big-hearted humanity of the average Italian and I think that once they get to know ‘immigrants’ as ‘people’ they will embrace them. Italy need immigrants – otherwise with a rapidly ageing population and the lowest birth rate in Europe, who is going to look after the elderly and work and pay the taxes to keep them in decades to come? People just will, eventually, realize this. It took quite a while for the UK to accept immigrants from its former colonies so I think we need to be patient.

Meanwhile, it’s vital to do all we can to humanize The Other, and to remind people that in another moment, in another country, by a random act of fate and history, The Other is us. This is why I believe so passionately in the power of stories and the importance of storytelling.

With the world the way it is and the innumerable distractions in daily life, how do you find the time and dedication to pursue something as ephemeral as an idea?

I find it pursues me! Elizabeth Gilbert’s latest book Big Magic, talks of how ideas come to you and you have a window of time in which you have the chance to realize them. If you take too long, you can find an idea has flown to the next person who might be able to give it life. I have experienced this. Writing is a long and hard process so the ideas that get realized are the ones that somehow stick and that you can’t get rid of, however many carpets you clean and countries you move through!

Tell us something that recently struck your funny bone (or share your favorite joke).

I’m not good with jokes, I am afraid. People’s essential nature and the absurdity of life is what makes me laugh.

If you could shout something from a mountain top, what would it be?

Let’s love each other – we are all the same under the skin.

If you’d like to read the original pdf of this interview or read previous interviews, please go to the Ampersand page.

© 2017 THE SIGH PRESS

None of the work published by The Sigh Press may be copied

for purposes other than reviews without the author and artist’s written permission.